Teaching Tips

| Site: | ART Online |

| Course: | Teaching Tips |

| Book: | Teaching Tips |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 21 November 2024, 5:16 PM |

1. Teaching bell handling

Combining strokes

Having got your novice ringer ringing the separate strokes proficiently, it is always a little nerve-racking handing over control of the bell so that they can put both strokes together. We share some helpful tips from Helen McGregor.

A balanced ringing style – which hand is doing most of the work?

Many learners don’t achieve a handstroke where the work is equally shared between the hands. What you often see, to a greater or lesser degree, is the right hand in charge of the sally, taking hold of it before the left, doing most of the pull and releasing it later than the left. Let’s look at the origin of the problem and then some ways to resolve it.

How long do I go on working on improving handling style

To help us as ringing teachers understand how long we should continue to work with learners we need to learn about the learning process. Learners will need a different approach to teaching when they are at the different stages of learning.

Teaching the rhythm of the lead

Helen McGregor explains an exercise which works very well at teaching the rhythm of the lead.

Do your learners struggle with changing the speed of their bell, particularly at backstroke?

By the time learners move onto Plain Hunt they need to be comfortable with speed changes so they can devote their attention to the bell’s path, not being overly distracted by the mechanics of getting the bell to ring in the desired place. This skill starts developing from the earliest handling exercise through to the end of Learning the Ropes Level 1 when the learner can raise, lower and set a bell. Many of the LtR Level 2 exercises contribute to the refinement of this skill and with a little imagination, you can find others too.

1.1. Combining strokes

Having got your novice ringer ringing the separate strokes proficiently, it is always a little nerve-racking handing over control of the bell so that they can put both strokes together.

Before you start, it is a good idea to adjust the length of the tail end so that the bell is rung under the balance, taking the pressure off the novice if they fumble or miss the sally and reducing your stress levels too!

A good place to start is for the novice to ring all the backstrokes with the handstrokes being introduced gradually – starting with just one. Which one depends on you and your novice ringer.

You can ask your ringer to ring the handstroke directly after the bell is pulled off, which is a natural place to start if your ringer has just mastered the handstroke pull off on its own, with you ringing the backstroke. In this case the novice ringer would begin by pulling off the first handstroke, transferring their hands onto the tail end and ringing the backstroke whilst you deal with all the following handstrokes.

Once the handstroke pull off and following backstroke is perfected ask the novice to catch ONE moving sally i.e. the novice pulls off at handstroke, rings the backstroke, catches one moving sally, the handstroke, rings the backstroke and you catch the next moving sally. Once perfected ask them to catch two consecutive moving sallies… but by now you may be already forgetting how many sallies you have told them to catch – is this next one yours or theirs? This is where regular patterns and verbal prompts become really useful.

You can ask your novice to ring every backstroke but only alternate sallies. Saying clearly after each handstroke – ‘yours’, ‘mine’, ‘yours’, ‘mine’- so everybody is clear about who is going to catch the sally next.

A pointed finger can also act as a visual prompt to reinforce whose sally it is next. Progress from this to the novice ringing two consecutive sallies and you ringing one. So after each handstroke, remind them aloud – this is your first sally, your second sally, this one is mine. Then the novice can move on to their ‘first of 3’, ‘second of 3’, third of 3’ and ‘mine’.

Alternatively, you can agree upfront a verbal prompt or instruction. For example:

- That stroke number 1 is ALWAYS the teachers and that you will count the handstrokes loudly and backwards.

- When their hands are on the sally to pull the first handstroke identify that as stroke no 3.

- The next handstroke is stroke number 2,

- And the last sally belongs to you.

- Then all you do is count – backwards – from a greater number and everyone knows whose sally is whose as you are always responsible for stroke number 1.

When you catch the sally, you can feedback to the ringer how powerful/underpowered it was when you caught it. You catching the occasional planned sally will give the ringer comfort/breathing space and will allow you to ‘get things back on track’ if there is any lack of control. The novice ringer will also be able to remind themselves of the feel of a good long straight down draw on the backstroke when they aren’t responsible for the sally and hopefully they will carry that on when they have to catch their own sally too.

Helen McGregor

1.2. A balanced ringing style – which hand is doing most of the work?

Many learners don’t achieve a handstroke pull where the work is equally shared between the hands. For the purposes of simplicity, I am going to assume the learner has the tail end in the left hand. What you often see, to a greater or lesser degree, is the right hand in charge of the sally, taking hold of it before the left, doing most of the pull and letting go later than the left. Let’s look at the origin of the problem and then some ways to resolve it.

One of the trickier parts of learning to handle a bell is getting the left hand to deal with both the tail end and the sally. The learner fears they will drop the tail end and so we get all manner of potential handling issues as they try to reduce this perceived risk.

One of these involves letting the right hand manage the sally, allowing the left time to deal with the tail end and then join it. The left hand then leaves the sally early, leaving the right to do the actual work.

Resolving the problem

Resolving the problem is something that’s ideally done during the process of learning to handle. However, we don’t live in that ideal world. We live in the real world with all its flaws. Please don’t come to my tower expecting to see nothing but perfect styles and hear nothing but perfect striking! I do my best, as do my ringers, but all are human with human imperfections and challenges.

So, what’s my take on this?

First, I will discuss with the learner (at whatever stage) why it is desirable that both hands/arms share the work. I make a bit of a joke about developing muscle only on one side, but we seriously consider the ringing action and that it is far better for the body to work as evenly as possible. In addition, the bell control at all stages (raising, ringing, lowering) will be more efficient. Depending on the individual, we may use a short video clip of their ringing to allow them to compare this to other people’s styles. It’s a fact that what someone feels they are doing may not be what they’re actually doing and video proof is what can convince them of this. I also find that before/after videos are really helpful. Sometimes they may like to keep copies for future reference – after all, whenever a ringer has a “weak point” in their handling it often crops up time and time again when they’re under stress, learning new things.

The next stage is a physical exercise. I ask them, with support, to ring the bell with just the left hand, keeping the other behind their back. Most require a good bit of support to have the confidence to even try this; I assure them my hand will be there as insurance. However, I am careful to add nothing at all to the pull. What normally happens is they struggle to pull off a bell they normal ring and are quite shocked. After a couple of slight fumbles with the sally due to them worrying about it, they quite quickly realise that they can ring the bell one handed as long as someone is there to make sure all is well.

I then ask them to ring the bell with the only the right hand working the sally. Again, I will put my hand on it to protect the stay if necessary. This time they usually find they can pull off with ease.

Essentially what we are doing is allowing the learner to discover for themselves how evenly they’re working. From this point the instruction is to focus intently on the left hand and be aware of its input. Then allow the right hand to stop pulling and just be there passively before gradually achieving a balance between the hands. The learner is encouraged to ring a few whole pulls on their own whenever possible, perhaps just a few prior to rounds starting or ringing the service bell on a Sunday as this offers private practice time. Then they’re asked, whenever ringing something that is straightforward for them, to repeat this exercise of focusing on the balance of work.

Don’t expect a quick permanent fix – it will take time and desire from the learner to correct the habit.

Remember, practice doesn’t make perfect, it makes permanent!

Heather Peachey

1.3. How long do I go on working on improving handling style

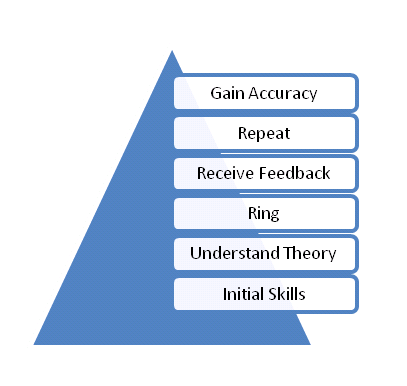

To help us as ringing teachers understand how long we should continue to work with learners we need to learn about the learning process.

Learners will need a different approach to teaching when they are at different stages of learning.

The different teaching techniques are all about coaching the learner. Because of this emphasis on coaching, the ringing teacher will be referred to as a ringing coach or coach.

As a learner becomes more skillful through practice, assisted by coaching support, three stages are passed through:

- Novice (Cognitive)

- Improver (Associative)

- Expert (Autonomous)

The Novice

During the cognitive or mental stage, the learner is attempting to understand the basic task and is figuring out the skill. They are learning to identify all the component parts of the skill and forming a mental picture of what is required.

Characteristics of the Novice

- Relevant movements to perform the skill are being assembled

- Major errors can be seen

- The style is fitful and jerky

Coaching requirements of the Novice

Basic instruction of explanation, demonstration and small step exercises to help the learner get the feeling of the actions. These will all help the learner get a mental picture of what is required. This is the time to get the foundation skills accurate. Learners are not aware of what they are doing wrong or how to correct errors.

Good feedback during this phase is important. Correct performances are infrequent at this stage and should be reinforced through external feedback and positive reinforcement from the ringing coach. Words and gestures are both relevant – a quick thumbs up can convey a lot.

The learner needs praise at this stage. This is the time the learner is ringing on an individual bell.

The Improver

This is the phase where the basic skills are becoming refined and the learner is linking the component parts into a smooth action.

Characteristics of the Improver

- Some errors are still evident

- The style is a bit hit and miss [sometimes they get it right and sometimes they get it wrong]

- The learner is starting to feel when they have got it right or wrong. They are starting to be able to correct their own errors

Coaching requirements of the Improver

This is the phase where continued feedback from the coach, coupled with frequent opportunities to practise, gradually shapes and polishes the performance of a learner. Practise on an individual bell is still important to enable feedback and reinforcement to be given. Practise of handling must be performed regularly and correctly.

Learners will be ringing on open bells and they need to ring on a variety of bells to help them develop their skills. The feedback they receive through the rope from the bell is an extremely good tutor.

The Expert

In this final stage of learning, errors are rare and performance has become consistent and fluid. The movements are well learned and stored in the long-term memory of the brain as a movement pattern. Bell handling has become automatic and involves little or no conscious effort.

Characteristics of the Expert

- Few small errors can be seen

- Fluid style

- Can transfer most learning to novel situations [the learner can cope with different bells easily]

Coaching requirements of the Expert

At this point the brain now has spare conscious capacity and it can give this spare attention to focusing on learning new things such as Call Changes, Plain Hunt and method ringing.

It should be noted that not all performers reach this stage,, which may explain why older learners who can be less coordinated than younger ringers can find it harder to develop their method ringing. They still have to use a large part of the brain to consciously control the bell!

To retain the new skilled performance at this level it must be constantly practised to reinforce the movement pattern. At this time coaches can diversify practice conditions; this is the time to take your learner on a ringing outing.

Pip Penney

1.4. Teaching the rhythm of the lead

Here on Alderney I have just spent a delightful week with five ‘ringing improvers’. They were able to handle their bell but their handling needed some polishing before they could progress onto Call Changes and take their first steps towards Plain Hunt. Leading was a great obstacle for all of them, however the following exercise worked very well at teaching the rhythm of the lead.

Ringing six bells with the students on bells 2 to 6, an experienced ringer rang the treble and led throughout. The students perfected their “leading” by hunting the back five bells from 6ths place down to 2nds and back so that the turnaround “at the front” was actually in seconds place and was lying over the experienced helper in first place (permanently leading) rather than attempting to lead by following a bell in 6ths place on the opposite stroke. In this fashion they got to 'feel' the rhythm of the turnaround, having a real target to aim at for their lie in seconds place at the end of their quick strokes.

Once perfected we called the experienced ringer off the front up to the back to ring an unmusical six but left the students on the bells they were used to and rang 'standard' Plain Hunt on five bells, leading opposite to the tenor. The resulting improvement in their leading was miraculous and accompanied by masses of smiles and remarks such as “That felt so different to my usual attempts and sounded great!”

1.5. Do your learners struggle with changing the speed of their bell, particularly at backstroke?

By the time learners move onto plain hunting they need to be comfortable enough with speed changes so that they can devote their attention to the bell’s path, not being overly distracted by the mechanics of getting the bell to ring in the desired place. Some will inevitably find it harder than others. This skill starts developing from the earliest handling exercise through to the end of Learning the Ropes Level 1 when the learner can raise, lower and set a bell. Many of the LtR Level 2 exercises contribute to the refinement of this skill and with a little imagination you can find others too.

Observation of experienced ringers shows that they do not always change their hand position on the rope when changing speed. When ringing ligher bells they achieve a quicker backstroke by bending their arms a little. Only when ringing a heavier bell do they shift up and down the tail end. The same is true of the handstroke, but here there is likely to be a small change in the position of the hands on the sally.

So, what’s going on? Efficient control of a bell relies upon the ringer having both the skills and experience to deliver the optimum amount of work on the bell, using a personally comfortable amount of physical effort. Simple physics tells us that the work applied to the bell is the force applied multiplied by the distance over which that force is applied. Ringers make changes to both force and distance as required. The experienced ringer does not need to think about doing so any more than a driver has to consider how hard/fast to turn the steering wheel. The novice does need to devote thought to the process and needs to develop a feel for both force and distance. Many start off by applying great force over a small distance, which is tiring and inefficient. Others struggle to apply enough force.

We teach the skill of a long pull to maximise the work achieved by the force applied. This of course has the essential benefit of better rope control and reduces the temptation to “snatch” at the sally.

As the novice progresses on to the stage of needing to make fine adjustments in order to vary speed we must ensure they have the physical skills to control the speed change. These are the same skills as the start of ringing down and the end of ringing up. Ring a bell yourself or have someone else do it and show natural ways of achieving speed, perhaps start by ringing a bell part down and back up again. Have learners watch, discuss and then experiment on single bells, seeking to refine the basic skills they have developed to date. Encourage them to consider the effectiveness of both moving the hands up/down the tail end, altering the positioning of the hands on the sally and ringing with arms straight, moderately bent or very bent. You may find it useful to consciously ring different weight bells for a dodging exercise yourself and discover what you do on various bells.

Having said that, it is absolutely essential that novice ringers learn the skill of ringing with the maximum distance of pull possible and learn to make quick and efficient alterations to their tail end length at the correct point in the pull, i.e. before the rope starts to rise to the backstroke and not whilst their hands are up in the air. It may be that they find this easier on a middle to back bell than on a light one. Having developed this skill they will be able to deal with pulling off a bell which has a tail end that is much too long or with a bell that suddenly drops for whatever reason and they will be well set up to learn to efficiently control bigger bells. Later they will settle to their own comfortable style, using the range of pull-length that suits them and the bell they’re ringing – but they have to “walk before they can run”.

|

|

Once the learner can comfortably change speed at will on a single bell, they need to practise it at normal ringing rhythms. There are many exercises which can be used for this – here are just a few:

- Follow the leader: offer a bell to follow who will take the learner on a journey of varying speeds.

- “Hunting” through static bells, i.e. the rest of the ringers stay in rounds sequence and allow the novice to ring in 2nds, 3rds etc between them. Hunting up/down can be separated by instructing the novice to hunt to 5ths and stay there. Then on an agreed cue, starting at backstroke, they hunt down to lead. This is a good way of emphasising the three speeds of hunting without them thinking about finding bells to follow.

- Call changes, changing at backstroke as well as at handstroke.

- Dodgy call changes.

- Long and short place making (Kaleidoscope) again changing at backstroke as well as hand.

- Mexican Wave.

Heather Peachey

2. The foundation skills

Steps to ropesight

Acquiring that elusive skill known as ropesight can be a frustrating time. In her teaching tip, Heather Peachey believes you can’t specifically teach or learn ropesight. What you can do is provide the best opportunities for the skill to develop, whilst reassuring learners that they will develop it at their own pace.

Developing listening and striking skills

Listening is one of the foundation skills of ringing. Without the ability to hear their bell it is impossible for a ringer to reach their full potential. New ringers frequently have difficulty identifying the sound of their own bell. This article provides a few tips on how to help your ringers hear their bell and develop the good rhythmic ringing we all want to hear.

Teaching Call Changes

Most ringers are taught Call Changes after learning to ring rounds. Call Changes may be thought of as simple but there is more to them than might be imagined. Which skills does your ringer need to have or develop before learning to ring Call Changes?

Teaching Call Changes – putting it all into action

Putting into action the skills discussed in the previous article. How to make the first moves a success, how to use feedback to improve accuracy and how to move onto more complicated changes.

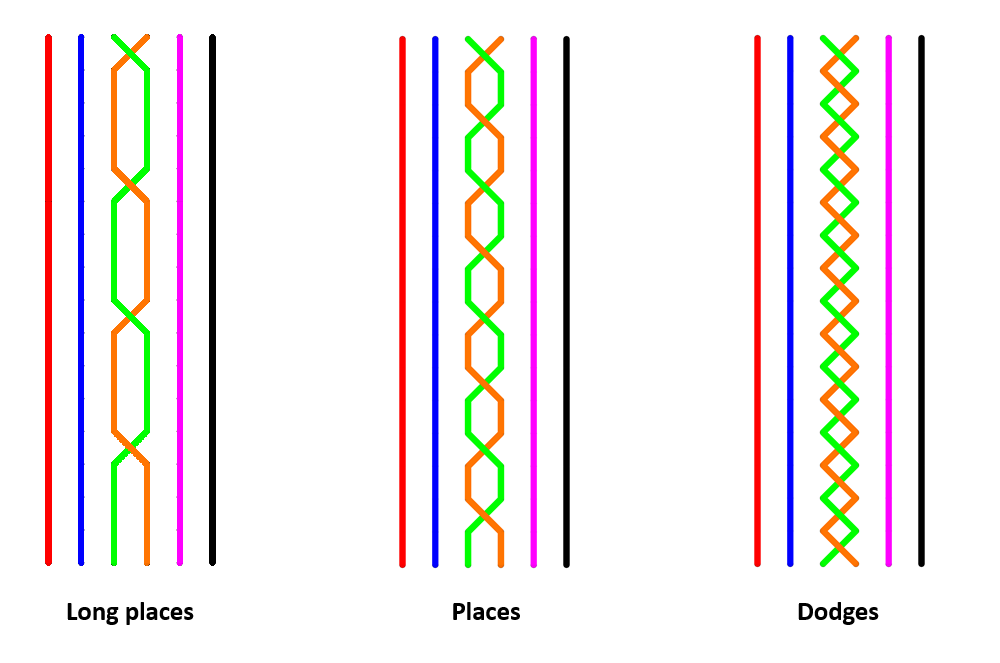

Teaching Kaleidoscope Ringing

Kaleidoscope ringing is a series of exercises made within two places. The simplest form is long places, four blows in one place. This is followed by place making with two blows being rung in each place and then by dodging. Kaleidoscope ringing helps a new ringer hear their bell and identify which place they are ringing in.

Advanced Kaleidoscope Ringing

Moving on from basic kaleidoscope works, there may be times when more advanced sequences may be useful to your band. When might this be?

A dedicated foundation skills practice

Pam Ebsworth had a number of teachers who had recently attended an ART Module 2 day course. Pam was wondering how to give these teachers more teaching practice. The problem was that these particular teachers were not Tower Captains and were finding few opportunities to teach at the necessary level. After discussion with other ART mentors it was decided to hold a dedicated Learning the Ropes Level 2 practice.

2.1. Steps to ropesight

Acquiring that elusive skill known as “ropesight” can be a frustrating time. I believe you can’t specifically teach or learn “ropesight”. What you can do is provide the best opportunities for the skill to develop, and reassure learners that they will develop it at their own pace. The teacher needs to watch out for sticking points and try to find interesting, creative exercises that suit the occasion to avoid learners becoming dispirited.

The process should begin as early as Learning the Ropes Level 1. Yes, the primary focus is on actually learning to control a bell, but at the same time the learner should be encouraged to watch other people ringing and guided in how to do so. The need to look at the hands and faces of the other ringers is not as obvious as experienced ringers may think. I discovered relatively recently the reason one of my ringers has an ingrained habit of looking up. As a conscientious learner she spent many hours, while sitting out, trying to watch what was going on and acquired a habit of looking up and watching the sallies descend. Despite frequent reminders and knowing it’s unhelpful, she still feels pulled to default to this when “lost” and felt quite uneasy when visiting a tower with a low ceiling because the sallies disappeared from view.

Guided exercises in watching

These are best done from a standing position to discourage looking upwards.

- Watch a skilled ringer by scanning between hands and face. Notice when in the stroke the bell sounds. Notice the point the hands are momentarily stationary; it’s after the hands rise with the tail end or sally, just before the ringer consciously draws the rope down (pulls). This is a good point of reference.

- Watch rounds on four bells. Explain that the 2 and 3 will now be asked to change places a few times. As they change, watch the hands of each ringer and try to see the order in which they are ringing.

- Watch the 4 cover over 2 and 3 making long places, short places and dodging (Learning the Ropes Level 2 exercises). Stand with the learner and have them state which bell the 4 is ringing over. This also prepares the learner for their own experience of these exercises so ensure the correct terminology is used.

- As soon as the learner can manage backstrokes on their own, have a bell ring just in front of them and one behind (i.e. rounds on three bells). This is a ropesight development exercise, not a speed control one, so the other two bells must allow the learner to dictate the pace. Have the learner actively look and listen, developing an awareness of seeing and hearing the timing. Repeat with handstrokes and later with both strokes. Remember, these exercises complement the single bell work, not replace it and the learner at this stage is not responsible for keeping perfect timing! The purpose is to introduce ropesight, the rhythm of rounds, hearing your bell in amongst others, responses to “treble’s going” and “stand”, and to add in variety to the experience of learning bell control at points when adult learners often feel they’re struggling to make progress.

Kaleidoscope Exercises and Call Changes

As soon as a learner can ring rounds reasonably well, start to introduce a range of Kaleidoscope exercises and Call Changes (Learning the Ropes Level 2). Aim to develop the ability to follow different bells as well as listen to the sound that’s produced. Encourage visual scanning of all the other bells that are ringing. Point out that as soon as you’ve committed to a backstroke or handstroke you cannot alter that stroke – so immediately start scanning for the next bell to follow rather than watching the bell you’re already following for too long. Additionally the learner should gain an understanding of place in the row and learn to lead with a good rhythm.

Covering by ropesight

Using a band of five stable ringers plus the learner, place the learner on the 4, 5 or the tenor, depending on their physical ability and weight/go of the bells. The reason for having six bells ringing is to provide a six-bell rhythm. Ask the learner to attempt exercises such as:

- Covering over the two bells immediately before them. These two bells will have been asked to swap increasingly randomly (good exercise in planning and communication for these two ringers).

- Covering over three bells who are plain hunting or whatever you wish.

- Covering to Plain Hunt on 4 and 5 bells. If the learner can’t physically manage a back bell, then have them ring the treble and call the bells into a suitable change such as 234156. 234 can then plain hunt.

- Cover to Plain Bob Minimus.

- Cover to Cloister Doubles (Stedman Quick Sixes, where the double dodges in 4-5 are done by only 3 of the working bells, while the other two are repeatedly making thirds from the front).

- Cover to Stedman Doubles (as above, but any pair of bells can be at the back).

- Cover to Plain Bob/Grandsire Doubles.

Encourage both listening and looking to see who they’re following; learners will vary in which they find easier.

Explain that “seeing” is a ropesight skill which complements listening. Point out that you cannot wholly accurately place the bell merely by looking, but it’s the looking that gives you the approximate position and the listening that allows you to fine tune it.

Why look? Why not just listen?

Around this stage, if not before, some will notice that many experienced ringers appear not to look at all, instead seeming to find inspiration from the pattern on the carpet. Use this to prompt a discussion and exercises on the use of peripheral vision and an awareness of the other bells. It can be very useful to do some whole band exercises on this, by asking the entire company to look at a point in space and rely only on peripheral vision to strike rounds. It is not unusual to have better rounds than expected!

It’s worth pointing out that when you’re inexperienced or unfamiliar with what you’re ringing, using direct gaze along with peripheral vision can be helpful for two reasons.

- Other ringers will often give help via facial expressions and gestures.

- Teachers and conductors can tell from a ringer’s direction of gaze whether that person is “lost” or is trying to do the right thing but in the wrong part of a row. For example, a conductor might say “Sam, you’re dodging 3-4”; the trouble is Sam knows this, however the bell is actually around 4-5. Sam has not been helped at all by the comment – the information necessary was that the dodge was with the 2, not with the 5. Personally, when a learner needs only little assistance in change ringing, I like to stand out in a position where I can see their face. I can then see whether or not an error is one of knowing the place they are in, but failing to find it, or whether they’ve dropped off their “line”.

Heather Peachey

2.2. Developing listening and striking skills

Listening is one of the foundation skills for ringing. Without the ability to hear their bell it is impossible for a ringer to reach their full potential. New ringers frequently find difficulty identifying the sound of their own bell. This article provides a few tips on how to help your ringers hear their bell and develop the good rhythmic ringing we all want to hear.

From the very first lesson

We teach on tied bells so as not to annoy the neighbours with the sound of a random bell or bells ringing. However, we do need to start to make the ringer aware of the importance of listening to and hearing their bell right from the very beginning.

If you have a simulator in your tower and you are teaching a single learner you can provide the simulated sound of that bell ringing during the teaching process. If you are teaching several learners in the tower together this is not possible unless you have multiple computers and use headphones.

So how can we overcome this difficulty?

- Using a laptop with suitable software for the ringer to make the bell sound by pressing a particular key on the keyboard is a good starting point. Headphones can be used and the new ringers can take their turn at listening and striking exercises on the laptop when they are taking a rest from the immediate handling lessons. It is usually easiest for the ringer to hear the tenor to start with. After a session, use the “Review Striking” facility to emphasise the importance of accuracy and to allow the ringer to notice improvement in future sessions.

- While your new ringer is still learning to handle a bell they can attend a practice and ring individual strokes (back or hand) with the band so that they start to be aware of the sound of rounds. In both of these examples encourage them to identify the place in the row their bell is sounding and to start to count that place. If the ringer is struggling to identify the bell they are ringing, try using a familiar phrase to help identify the place. A commonly used one is “we all like fish and chips , I want some for my tea” .In this example the ringer is ringing bell number four in rounds and emphasising the fourth sound in the row with the words fish and for.

Now the ringer can ring an individual bell unaided

Once your new ringer can ring an individual bell without assistance they can start ringing with others. As the teacher you need to be certain that your ringer is identifying the sound of their own bell. One way of doing this is to start the ringer ringing rounds on three bells - start with them on the third and then let them ring the second. You can use the rhyme “Three – Blind – Mice” if they are struggling. The familiarity of the rhyme aids in the identification of the sound of their bell.

Many ringers can perform rounds on three accurately right from the start and can be moved on to rounds on four and then six on the first practice night. However, there are others who may take a few weeks to hear the sound and take ownership of what they are hearing.

At this stage ringing on a tied bell with a simulator is invaluable. If you don’t have a simulator in your tower a neighbouring tower may let you take your ringers to them for a few sessions on their simulator.

Listening and striking exercises with a group

Ideally, these exercises would not be practised on open bells but with a simulator.

- Setting alternate bells at backstroke and then getting your ringers to pull off and ring rounds is a challenging exercise for beginners and sometimes for experienced ringers as well. It provides variety and is fun to do.

- Facing outwards from the circle one ringer at a time so that the ringer is unable to see the bell they are following is useful. Ensure your ringers make the turn when the rope is up at backstroke, this will ensure there is no likelihood of getting tangled with a moving rope.

- Whole pull and stand for a whole pull, keep the tenor ringing for the whole pull while the other bells are standing. Then practice the perfect pull off each time.

An ability to control and hear the bell are both necessary to produce good rhythmic ringing. For rhythmic change ringing a knowledge of theory and ropesight needs to be added into the equation.

- Plain Hunting can be used as an exercise to develop rhythmic ringing; this is equivalent to practising scales on a musical instrument and should be repeated frequently when working towards good striking on a certain number of bells. For instance when a ringer is moving from Doubles to Minor, Minor to Triples or Major.

- Treble Bob Hunt with all the bells following the same line can be used when moving ringers on to Treble Bob or Surprise methods. It is false. The coursing order is Plain Hunt coursing order so there are no ropesight issues and ringers can concentrate on striking and rhythm.

- Kaleidoscope ringing can be used to help develop good striking. Long places [two whole pulls], places [a whole pull] and dodging can be combined to make different exercises. Work is done within two places and the ringing frequently returns to rounds in which it is easier for the less experienced ringer to identify their own bell. The changes can also be started on a backstroke.

Resource tips

The following YouTube resource describes ropesight using a dynamic diagram of Plain Hunt on five bells. At 1:25 in the video there is a slo-mo video recording of Plain Hunt highlighting ropesight from the treble.

Keeping track of where you are in the change. This article explains how ringers keep track of their place in a change through counting places, listening, ropesight and dividing the changes into hand and back. Originally published in The Ringing World.

Pip Penney

2.3. Teaching Call Changes

Call Changes is the skill that most new ringers are taught after learning to ring rounds. It may be thought of as simple but there is more to it than might originally be imagined.

What skills does my ringer need to have or develop before learning to ring call changes?

- To be able to ring rounds

- To be able to stay in the correct place

- To be aware of where their bell is striking in the row

- To be able to hear when the bell is out of place and be able to adjust to get back into the rounds

- Ability to ring quicker or slower [ability to hold up and check in]

Absolute perfection cannot be expected at this stage.

What theory does my ringer need to know before learning to ring call changes?

- Treble/Tenor

- Front/back

- Lead/lie/cover

- Up/down – in/out

- Concept of a row

- Concept of place in the row

- Concept of a whole pull

- Meaning of check/pull-hold up/check in

- Understanding of why change of speed is required to change place in the row

What teaching aids could I use to help my ringer understand?

The Call Change Toolbox has a ready-made PowerPoint presentation for you to use with your ringers to introduce these basic concepts in an interesting way. You will find also find Call Change worksheets for your ringers to use.

A white board is a quick and easy way to illustrate the way in which call changes work. A few rows written out and joined together with arrows can illustrate these concepts in a few moments. By joining the bells with lines you are in fact introducing your ringer to the visual representation of the “blue line” without having to even mention it by name.

What new information do I need to give my ringer before introducing Call Changes?

Before you undertake the teaching of Call Changes with your ringers you need to decide which method of calling you are going to use. The three different calls below all lead to the same change:

| Calling up | 1 2 3 4 5 6 | “3 to 4” | 1 2 4 3 5 6 |

| Calling down | 1 2 3 4 5 6 | “4 to 2” | 1 2 4 3 5 6 |

| Calling by place in the rows | 1 2 3 4 5 6 | “3rds place bell follow 4ths place bell” | 1 2 4 3 5 6 |

Teaching Tip

Whichever method you choose to use it is important that your ringer learns to identify what place in the row their bell is sounding at after every change. As an exercise ask your ringers to say their place number as they strike their bell. This will help reinforce the concept of which place they are ringing in.

Pip Penney

2.4. Teaching Call Changes – putting it all into action

Placing your band

Ensure you have a treble ringer who is leading well and a tenor ringer with a good sense of rhythm. Place competent ringers on either side of the inexperienced ringer.

For the very first Call Change it is easier for your ringer to work with the bells he is already looking towards and following in rounds, that is to say to get the ringer to move down a place out of rounds and up a place to get back into rounds. If you choose this option it means that the ringer cannot ring the 2, as, at this point in their ringing development they are unlikely to have learnt how to lead.

The first call – what does your ringer need to know?

- The call is made on the handstroke pull

- They will ring that handstroke followed by the backstroke

- The change of speed to get into the new place is made on the following handstroke

- The change of speed is for one blow only and then normal rounds speed is resumed

Explain to your ringer that this whole pull warning gives them the opportunity to adjust the intervening backstroke to enable the bell to be moved into the new place more easily, putting less energy in when preparing to move down a place. When ringing the handstroke more quickly, putting in more energy is necessary to make the bell swing higher in preparation for holding up the following handstroke when moving up a place.

The ringer needs to understand what happens at a call, which bells are affected, and in what way. So, if the call is 3 to 4:

- The 3 has to hold up, ringing more slowly to follow the 4 in 4th place

- The 4 has to check in, ringing more quickly to follow the 2 in 3rd place

- The 5 stays in 5th place but now follows the 3 not the 4

The use of questions to check understanding ensures the ringer has processed the information. For example: “when your bell is called to move down [or up] does it have to ring more quickly or more slowly?” This may seem obvious to the teacher but when first asked, this question may confuse new ringers.

Using questions to check understanding

When the ringing is settled ask:

- What place is your bell sounding in?

- Which bell are you following?

- Which bell is that following?

- Who is following you?

And when they have advanced a little:

- Which bell is leading?

- Which bell is behind?

And even:

- What is the order of the bells?

Following the call

Observe how accurately the call was executed.

Feedback to the ringer:

- Feedback is used to reinforce what is wanted – so tell them if their striking the change was accurate and if the following back stroke was accurate.

- Feedback is used to change and improve things – so tell them where they were struggling and it was not sounding right

Give the ringer the information to improve performance at the next attempt – for example – “next time put a little less weight on your backstroke so that it is easier to get the following handstroke down into the new place”.

Give the ringer opportunity to repeat the action.

Give feedback again – improved? Still having problems? Repeat these two simple changes until the accuracy of the striking improves.

This whole process can then be repeated again by calling the ringer to move up a place, i.e. looking to his or her left to move up and to the right to move down again into rounds.

Moving on beyond the basic moves

When a ringer can accurately move up and down a place and return to steady rounds, they are ready to move on to more complicated sequences. The ringer can be introduced to common sequences such as:

Queens: 1 3 5 2 4 6

Tittums: 1 4 2 5 3 6

Whittingtons: 1 5 3 2 4 6

Whilst ringing more complicated sequences the teacher should use questions such as “what place in the row is your bell sounding?” This process continues until the teacher is certain that the ringer is always aware of their place in the row. Another ringer could be used to stand behind and ask these questions.

Reinforcing the sense of place

To help reinforce the sense of place in the row a ringer can be asked to call simple Call Changes, for example to call themselves up and then back down a place or two places.

A ringer who finds this exercise easy can move on to calling more complex sequences such as the bells into Queens or Tittums and back into rounds.The use of exercises such as these can give the teacher an indication of the ringers who already have a good idea of where each bell is at each call.

The ringers can be asked to say the number of the place they are ringing in. Starting with the bell leading the ringer says “lead or first”, the bell in seconds place then says “second”, this progresses around the circle until all the ringers have said the number of the place they are ringing in.

Using variations to reinforce and to improve skills

Once the ringer is confidently ringing Call Changes and is:

- Striking accurately

- Aware of their place in the row

- Understands the calls and is not making mistakes

Variations can be added this will develop skills and provide interest:

- Call by place in the row

- Call and change at backstroke

- Call by ringers' names

- Ring dodgy Call Changes – a call proceeded by a dodge! This variation demands an increased level of bell control to strike accurately and is a good exercise to use to work on accurate striking

- Call from rounds directly into a known sequence such as Queens. This requires an increased level of bell control but once the striking is good can be used for ringing at weddings and other occasions

Direct your ringers to the Call Change Toolbox for ringers where they can learn more of the theory and practice of Call Changes.

Pip Penney

2.5. Teaching Kaleidoscope Ringing

Kaleidoscope ringing is a series of exercises made within two places. It can be started at handstroke or backstroke.

The simplest form is “long places”, 4 blows in one place. This is followed by “place making” with two blows being rung in each place and then by “dodging”. Each one demands a higher level of bell control than the previous one. They are best introduced in this order.

The aim of the exercises are:

- To refine bell control

- To refine listening skills

- To develop accurate striking and good rhythm

- To reinforce the concept of place

If new ringers are to move forward with change ringing they need to be able to hear their own bell and identify which place they are ringing in. Conventional call changes, called by asking two numbered bells to swap places, do not develop these skills.

Why Kaleidoscope Ringing?

In kaleidoscope ringing, the bells move into and out of rounds. As the sound of rounds is familiar to the ringer, any inaccuracies in the striking can be more easily identified. If the ringer is able to identify the sound of the bell in simple changes, he or she will be able to hear their bell in more complex sequences as their ringing progresses. In addition:

- Instructions are easy to follow

- Easy place identification for the ringer

- Changes can be started at back or handstroke

- Practise leading for only one whole pull at a time

- Simple introduction to following a line

- Changes of place can be memorised

- Innovation and variety to maintain and develop foundation skills

- Provides a basis for moving onto hunting on 3 bells

The basic works

- The conductor calls the bells to start on a handstroke or a backstroke

- The exercises continue until the conductor calls the bells involved to stop

- It is advised to start from rounds to begin with, with only one pair of bells working at a time

- When the striking is good, exercises can be undertaken with two or more pairs of bells involved

- When these basic manoeuvres have been mastered they can be combined to form a more advanced exercise. Different exercises can be rung at the same time in different pairs of places, not necessarily starting from rounds

Starting at backstroke is good preparation for moving the bell at backstroke when starting to learn Plain Hunt. It can also give practise at backwards leading.

Why not try this with your ringers?

In big change, little change all pairs swop for a whole pull, before returning to rounds for two blows. Then just the inside bells [2,3,4,5] swop places for a whole pull before returning to rounds. More bells are involved with the changes; the ringers have to concentrate hard to know when to move up or down a place. Ringers should be encouraged to think of the place they are ringing in, for example the 4 would be thinking 4th, 4th, 3rd ,3rd, 4th ,4th, 5th 5th, 4th 4th etc. This can be rung for service.

Resource Tips

- Kaleidoscope Ringing – A Change Ringers Alternative to Call Changes is available from the Central Council online shop.

- Images and explanations for you and your ringers are available from the Method Toolboxes.

Pip Penney

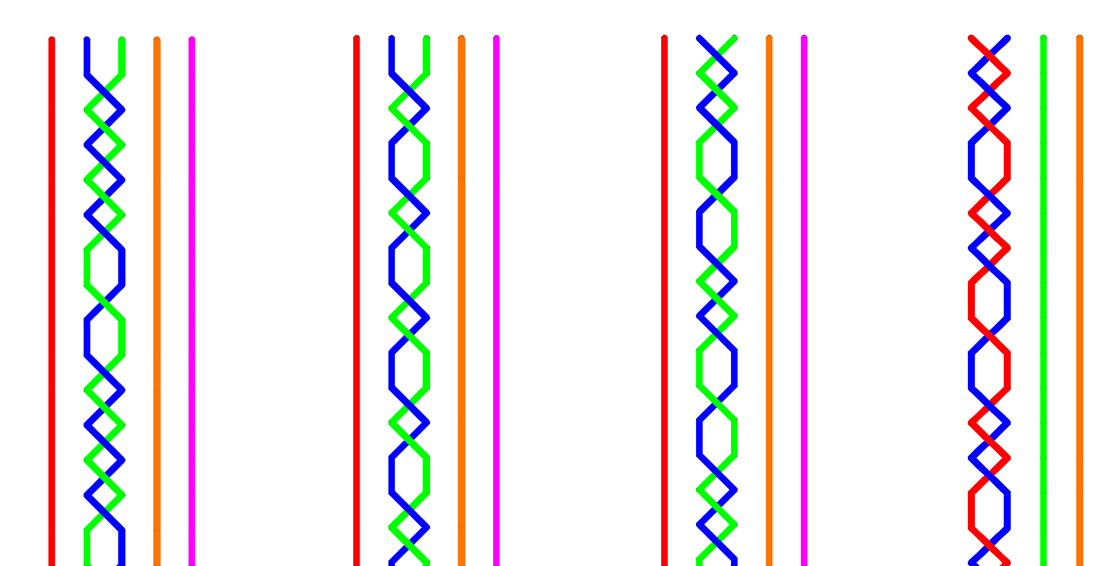

2.6. Advanced Kaleidoscope Ringing

Last time we looked at teaching the basics kaleidoscope works. But there may be times when more advanced sequences may be useful to your band. When might more advanced kaleidoscope ringing be useful for developing skills in my ringers?

Using Kaleidoscope ringing

There may be times when the band meets short, or at least is short at the beginning of practice before everyone arrives. Advanced kaleidoscope sequences may be used to practise the skills for ringing certain sections of methods that will be rung later.

There may be a time when you wish to emphasise the need for accurate striking to your ringers. These sequences provide a form of ringing where the ringer finds it easier to hear their bell as the bells frequently return to the familiar sound of rounds.

You may run a band where there is insufficient experience for your ringers to move on to method ringing. Kaleidoscope ringing provides more variety for your ringers and can be used to ring for services and other ringing performances.

It is possible for a ringer to learn for example: Stedman back work within two places (left), Stedman whole turns (second), Yorkshire Places (third). Cambridge front work (right) could also be learned in this way with one bell ringing the line and the other bell having the more difficult task of fitting in around it.

These exercises familiarise ringers which pieces of ringing which they will meet later on when they move on to ringing methods.

Kaleidoscope ringing on higher numbers

Towers with higher numbers of bells sometimes find themselves in a position where they do not have sufficient advanced ringers to ring methods on the all the bells. Kaleidoscope ringing can provide a useful addition to ringing call changes providing more variety and consequently helping to maintain interest. It can be used with different skills levels, the more advanced ringers ringing sequences which are part of methods or which include dodging. Less able ringers could be put to ring Long Places with four blows in each place.

Why not customise your own Kaleidoscope sequence?

So start with the sequence might have a “separator”. So for example a sequence can be rung in 1 /2 with the 3 staying in thirds place and the 4 and 5 ringing a different sequence.This has the advantage of stabilising the ringing by keeping the 3 and the 6 in their home places and gives both the ringers of those bells an opportunity to learn to cover. As the ringers skills progress, the sequences can made more complex. For example, the teacher might start with the bells in 2/3 making long places, 4 staying in 4ths place and the bells in 5/6 making short places and move on to bells 1/2 treble bob hunting or ringing Cambridge front work with the bells in 3/4 making places and the bells in 5/6 staying still.

If your band has insufficient capable ringers to ring methods or you wish to build skills in certain ringers you can make up your own sequence to suit your band. Give it a name and ring it for service. Why not name it after your tower or one of your ringers! St Peters Places or Sheila’s Shuffle for example!

The possibilities are endless! Set your imagination free!

Direct your ringers to the Foundation Skills Toolbox where they can learn more about Kaleidoscope Exercises.

Pip Penney

2.7. A dedicated foundation skills practice

At Rattlesden, Suffolk, ART Assessor Pam Ebsworth had a number of teachers who hadrecently attended an ART Module 2 Day Course Teaching Elementary Change Ringing. Pam was wondering how to give her teachers more teaching practice. The problem was that these particular teachers were not Tower Captains and were finding difficulty getting opportunities to teach at the necessary level. After discussion with other mentors it was decided to hold a dedicated Learning the Ropes Level 2 practice. In line with the Level 2 syllabus, this practice would concentrate on Foundation Skills and ringing with others. A date was fixed and the day attended by three mentors, five teachers and various new ringers.

- Controlling the bell

- Listening to the strike of the bell

- Following different bells when changing places

- Understanding the concept of place in the row

- Calling the bells to stand

- Understanding the concept of place in the row

- Starting to give simple instructions

Controlling the bell

Teacher number one used ‘whole pull and hold on the balance’. She taught when to pull off visually and how to listen for the strike of the bell. This is an excellent introduction to leading skills. The new ringers picked it up very quickly!

Listening to the strike of the bell

‘Ringing blind’ in rounds was used to help with listening skills. After learning to turn around while ringing, each ringer did this in rounds until the whole band was ringing ‘blind’. The task was taken to a more challenging level when Call Changes were added!

Following different bells when changing places

Teacher number three explained the theory of Call Changes, how adjacent bells change places and explained that bells can be called by the ‘up’ or ‘down’ method. He used numbered door knobs to explain this theory. Practice was then given using individual Call Change activities using the least preferred calling method! It’s good to be put out of your comfort zone.

Developing a sense of place in the row

The fourth teacher explained the concept of calling changes by calling by place in the row rather than by the number of the bell. Interestingly enough this proved quite straightforward for the new ringers and they took to it more easily than some established ringers do. It is important for ringers to start to be aware of their place in the row from early in their ringing career as without this awareness moving on successfully to method ringing will be more difficult.

The teacher also taught the ringers how to move out of the way and back again while the treble moved up to 5ths place and back down again. Apart from learning the speed changes without worrying about which bell to follow, this is very useful for teaching ‘place’ as the treble follows the 2 in 2nds place, the 3 in 3rds place etc. It also challenges the ropesight of the other ringers!Another teacher had the ringers walking Plain Hunt on three bells down the church aisle. The person/bell moving down stepped in front of the person/bell moving up. This covered what most of us would consider to be fairly advanced theory but yet again the new ringers soon grasped the idea.

Starting to give simple instructions

The fifth teacher explained to the new ringers that ringing instructions are generally made when the treble handstroke is just starting. The action then takes place at the following handstroke. He explained that the call needs to be loud enough for everyone to hear. The new ringers practised calling ‘stand’ from rounds and achieved this very quickly.

The outcome

The practice turned out to be a very interesting and challenging session. It certainly made all the teachers and mentors change their ideas about how much information relatively new ringers can absorb when concepts and activities are presented in an interesting and different way. Although the practice session was primarily designed for the teachers to hone their teaching skills, a lot of learning took place by the new ringers even though the bells were actually rung for less than half of the time.

3. Teaching method ringing

How to teach a method

Before moving on to learning any method it is important that ringers have both the necessary foundation skills in place, and understand the theory of the method they are to ring. Learn what these are and how to teach them.

Teaching ringers to cover

Building the skills required to cover confidently and well with the goal of ringing a quarter peal on the tenor to a doubles method.

Teaching ringers to plain hunt

All the things that need to be covered in order to get your ringers confidently ringing Plain Hunt – theory, bell control, ropesight and place counting.

Introducing Plain Bob Doubles in easy stages

When learning Plain Bob Doubles as their first method, a ringer often finds that being able to recall the four leads of the plain course whilst ringing is too much. By using short learning methods to introduce the various different pieces of work in Plain Bob Doubles, the ringer does not have to be able to recall the whole forty changes of the plain course initially.

Introducing the bobs in Plain Bob Doubles

Splitting new skills into smaller bits allows the learner to tackle a new skill in bite-sizes chuncks. Here are two strategies to help your student learn the effect of a bot, both involving repeating selected works.

3.1. How to teach a method

Skills

Before moving on to learning a method (in this case, Plain Bob Doubles) it is important that ringers have the necessary foundation skills in place.

Ringers can gain valuable ropesight by having already learned to cover, or ringing the treble to touches of plain methods. Ringers who have completed Level 3 of the Learning the Ropes scheme will have already rung two quarter peals, one on the treble and one on the tenor.

A good sense of rhythm on five bells is also helpful. This skill can be developed by plain hunting starting on lots of different bells, as this helps the new ringer become familiar with spotting after bells on either side of them. So when ringing the third, the after bell is the second – on the ringer’s right (in a clockwise tower). Whilst if they’ve started on the second, their after bell will be the fourth – on their left.

Any experience your ringer can gain with dodging is valuable. If ringers can gain confidence with both dodging over and under at hand and back, they’ll already be familiar with the action of dodging when it occurs in a method.

Before ringing any method, ringers need to be able to successfully count their place. If this is still a struggle, you can help by standing with them as they hunt the treble and counting their place out loud for them. Once they are hunting reliably, they can count alongside you, and finally just count by themselves.

Theory

Ringers sometimes feel daunted by all the theory they need to learn when they first start ringing methods. It’s helpful if they can get into the habit of learning things away from the tower. However, some ringers can be quite resistant to this idea to begin with and teachers may have to try various strategies to persuade them.

So what’s new to learn?

- The concept of the blue line and how the method works

- The order (or circle) of work

- The concept of start or place bells

- Rules for passing the treble

- The concept of the grid can be introduced for very keen people

The first time a method is learned, it is worth holding a dedicated theory session for the ringers, perhaps before practice. Or teachers may wish to hold a separate session and invite other local ringers, or run something for the local ringing society.

The Method Toolboxes are available on this site. They include:

- PowerPoints covering the theory of Plain Bob Doubles.

- Wall charts of a plain course and touches.

- Games and quizzes which can be printed off and given to a ringer to complete before the next practice.

Smart phone apps

The Simulator Toolbox contains links to apps that allow ringers to practise methods on their Android device or smart-phone. Ringers can turn on bobs to learn touches, or just tap through a plain course. The app tells the ringer when they are correct and is easy to use!

3.2. Teaching ringers to cover

Covering develops a ringer’s ropesight, the ability to see bells changing below them, and gives them a feeling of the rhythm of the change.

Skills

To cover confidently cover well your ringer needs to develop four skills:

- Listening – the ability to hear their bell amongst others

- A sense of rhythm – getting the feeling

- Awareness of their place in the row – place counting

- Ropesight – the ability to identify which bells to follow

Preparation

Your ringer is ready to learn to cover when they can:

- Ring rounds

- Hear what place their bell is sounding in

- Recognise when their bell is out of place in rounds

- Adjust their bell to get it back into rounds

- Ring the tenor

Ringing the tenor in rounds will help the ringer get their ear tuned in to listening to themselves in 6th place. Always make sure the ringer is counting their place in rounds. Using a simulator to allow a ringer to ring rounds in 6th place is a useful exercise. The latest software with moving ringers which can be shown on a screen or large TV are particularly useful at this stage.

There is little theory required when teaching covering. However, remember to point out that when covering to Plain Hunt or methods, the bells change below on a backstroke for odd bell numbers and handstroke for even bell numbers.

Putting it into action

Teach your ringers to cover in graded steps making each step easier to achieve:

- Call Changes

- Place making, dodging, Kaleidoscope sequences

- Plain Hunt on 3, 4 and then bells

- On 8 bells steady ringing with 768 behind to develop 8 bell rhythm

- Methods – plain courses, touches and then different methods

Introductory Exercises

The first opportunity for the ringer to do this is when ringing call changes; the ringer need not be ringing the tenor at this time. Kaleidoscope ringing also provides an opportunity for a ringer to cover to two bells making long places, places or dodging. To find out more about Kaleidoscope Ringing see Level 2 – Teaching foundation skills. Ringing the tenor in rounds will help the ringer get his or her ear tuned in to listening to themselves in 6th place. Always make sure the ringer is counting their place in rounds.

Covering to Doubles

Once the ringer can cover to rounds and Call Changes and Kaleidoscope Ringing they can move on to covering to Plain Hunt. Let them stand behind the tenor ringer to learn to follow the ropesight. If the ringer finds difficulty in covering to Plain Hunt on 5 then it is possible to start with covering to hunting on 3 or 4 bells.

Once the ringer is striking well to covering to Plain Hunt on five they are ready to move on to cover to methods. Start with plain courses moving on to touches when the striking is accurate. Plain Bob has a coursing order most similar to Plain Hunt and may be a good method to start with. However other methods where a smaller number of bells come to the back may also be useful.

Cloisters Doubles or Stedman quick sixes is a method where only three bells (the 3, 4 and 5) come to the back providing easier ropesight for the learner – see diagram to the right.

Can ropesight be taught?

Ropesight is a visual skill. It is a skill learned through experience and cannot be learned from a book. The eyes gradually learn to pick up moving ropes in the periphery of their visual field. For this skill to develop, practice is needed and this takes time. Ringers will need varying amounts of practice to develop ropesightl; some will find it easier than others! It is our job as teachers to provide the amount of practice in the appropriate environment with sufficient support to ensure our ringers gain the skills required.

Teaching Tips

- Get the ringer to stand behind the tenor ringer to watch and learn

- During early attempts stand with the ringer to assist with the ropesight if the striking strays. A visual prompt, pointing or gesturing in the right general direction of the bell which should be followed can assist

- By grading your teaching starting with something the ringer can do easily will enable them to achieve success. Some ringers will not need all the smaller steps or can move through them very swiftly

- Remember all ringers will be different and you need to keep your teaching flexible

- Making sure your ringer experiences success which will boost their confidence

- Some ringers learn to cover by ringing with the rhythm and developing the ropesight over time and some pick up the ropesight earlier but need time to develop the feeling of the rhythm

Ringing a quarter peal on the tenor

You should ensure that your ringer is not merely memorising the pattern of bells coming to the back before they ring their first quarter peal. To be certain that they have developed the skill of covering make sure they can cover to touches of at least two different Doubles methods.

Once your ringer has developed the ropesight for covering and following different bells while staying in the same place themselves they will be ready to move on to developing their ropesight whilst their bell is changing place. They will be ready to move on to learn to Plain Hunt.

Pip Penney

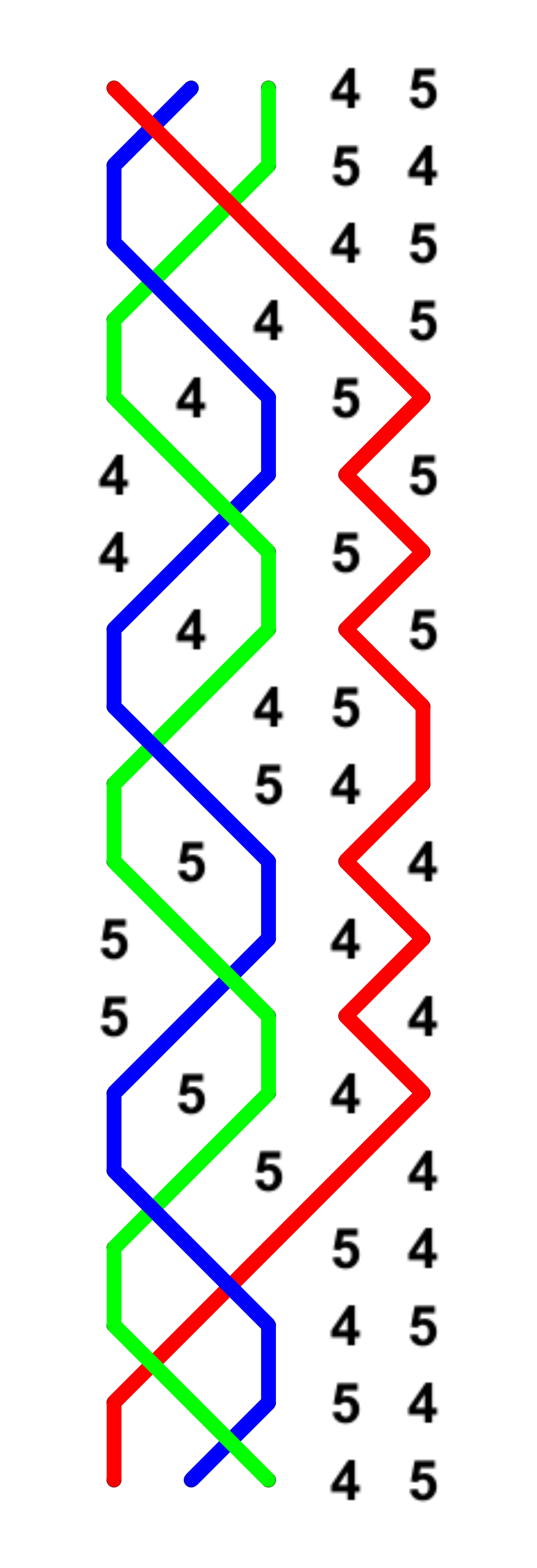

3.3. Teaching ringers to plain hunt

What new theory will my ringer need to know?

Hunting is all about ringing at three different speeds:

- Slower than rounds to hunt up

- Quicker than rounds to hunt down

- Rounds speed when lying behind

New jargon:

- Hunt out, hunt up, or run out

- Hunt in, hunt down, or run in

- Introduction to the blue line

- Chance to introduce course and after bells

Getting the rhythm

The more your ringer can develop the rhythm of hunting the more easily they will be able to develop ropesight.

With accurate rhythm their rope will be in the correct relationship with the other ropes. The initial aim is for the ringer to ring good rhythmic Plain Hunt with Plain Hunt coursing order.

The development of this rhythm is a practical skill and will take time and repetition.

How many bells should I use to teach?

This is really down to you, your preferences and the ringer you are teaching. Some people start on three bells some go straight to 5. Those who teach via even bell methods will probably use 4 and then progress to 6 bells. The rhythm on an even number of bells feels quite different to on odd numbers. This is because on even numbers the bells lie at the back handstroke/backstroke, the first quick blow down from the back being a hand stroke, whilst on an odd number the bells lie at the back at backstroke then handstroke, the first quicker blow coming down from the back is at backstroke.

The feeling of both will need to be practised by your ringer but teachers will vary on when to introduce this practice. If the ringer learns to hunt on 4 bells early on they are building skills to help them move onto Minor methods later. If the ringer works only on odd bell hunting to start with they are likely to improve more quickly at that particular skill but will not have experienced the even bell rhythm which will help them move onto Minor later. Some teachers prefer to use odd bell hunting as they can be rung with the tenor behind which gives stability to the change as a whole and can be used with a less experienced band.

Building the skills – preparatory exercises

- Practise ringing at three speeds on a tied bell or using a simulator and following another ringer (rounds speed, faster than rounds speed, slower than rounds speed.)

- Practise changing speed. At handstroke by checking the rise of the sally to ring quicker and letting it rise more to ring slower. At backstroke by taking rope in at bottom and letting it out at the top.

- Revise leading with an open hand and closed backstroke.

Place counting

The ringer should be encouraged to count their place in the row at all times. This is a hard skill and ringers are often resistant to attempting it. Even those ringers who are trying may find themselves struggling to count their place continuously.

Resource Tip

The theory of hunting can be explained with a white board and pens or you can use the PowerPoint slides which can be found in the Method Toolboxes. There are other resources such as charts and worksheets to help your ringers absorb the theory.

Pip Penney

3.4. Introducing Plain Bob Doubles in easy stages

When learning Plain Bob Doubles as the first method, a ringer often finds that being able to recall the four leads of the plain course whilst ringing is too much. By using short learning methods to introduce the various different pieces of work in Plain Bob Doubles the ringer does not have to be able to recall the whole forty changes of the plain course initially.

Shorter methods make the whole task of learning a plain course less daunting. They can often be learned over a very short period of time, sometimes in one practice session, leading to a sense of achievement and confidence in ability to understand and recall the method. They also provide variety for the supporting ringers.

More information and cribsheets for each of these methods can be found in the method toolboxes.

Bastow Little Bob Minimus

This is very short, being only twelve changes long, making it easy to memorise. It is very simple and provides an excellent introduction to method ringing. The order of work for the working bells is dodge 3/4 up and dodge 3/4 down. Download cribsheet.

The ringer can usually ring this straight off if they have been familiar with looking at blue lines when learning to hunt and they can frequently perfect it within a few sessions. It may take as little as one practice to master and move on.

This method is also straight forward for the supporting ringers to learn. Only two other method ringers are required! If ringing on 6 bells, the 5 has to cover to just three working bells as the treble only makes seconds throughout. The tenor ringer can follow the 5 and practise ringing at the end of the change.

Bistow Little Bob Doubles

This short method is sixteen changes long and includes a third piece of work from the plain course, long fifths [four blows behind]. As with Plain Bob Doubles the bell ringing long fifths rings over the two bells dodging in 3/4. A ringer is likely to be familiar with this technique if they have previously learned to cover to a pair of bells dodging in earlier skills building exercises. Download cribsheet.

Wotsit

Wotsit is a short method devised by the Whiting Society. It is 18 changes long.

The working bells (2, 3 and 4) dodge 3/4 up, 3/4 down and make seconds. The treble hunts to thirds place and back to the front, whilst the 5 makes alternate fourths and long fifths over each pair of bells in turn as they dodge in 3/4. Download cribsheet.

Doodah

Doodah is another short teaching method devised by the Whiting Society.

The 2 makes seconds and long fifths alternately. The 3 and the 4 dodge 3/4 up, make long fifths and dodge 3/4 down. The treble hunts to fourth place and back to the front.

Within these four short methods there is an opportunity for the ringer to familiarise themselves with the four pieces of work in a plain course of Plain Bob Doubles. Download cribsheet.

Teaching Tip

These short teaching methods should be explained in the tower before the ringer takes hold to ring. Going through them with the ringer will help them to understand how a blue line can help them to learn a method. However, once this concept is understood the ringer should be encouraged to learn methods out of the tower, before arriving at practice.

Pip Penney

3.5. Introducing the bobs in Plain Bob Doubles

Splitting new skills into smaller bits allows the learner to tackle a new skill in palatable bites. This is valuable for all learning styles, in particular for those whose preference is kinaesthetic learning, i.e. learning more through hands-on experience than by verbal or visual instruction. To have the most flexibility you need to let go of the tradition that suggests that all touches must be true or at the very least start and stop in rounds. Practise what you need to practise in the most time-effective manner.

Here are two strategies for chunking the learning of calls, both involving repeating selected works. Whilst most will teach only bobs, do remember that Plain Bob Doubles does have a specific single (place notation 123). It’s very useful as it introduces the concept of more than one type of call early on and it also permits a wider variety of 120s to be rung. It has featured in the Ringing World Diary for a very long time but many ringers don’t seem to know about it.

Choose to put in calls which have a specific effect on the learner’s bell

The simplest example of this is to call two consecutive bobs.The 2 will run in twice – it merely plain hunts, but the difference is that the ringer must be mentally ready to either dodge 3-4 down OR run in if a bob is heard. Similarly the 3 with either make seconds or run out. The purpose of this exercise is that whenever they approach a piece of work they remind themselves of the work if there’s a call.

This can be developed in several ways. You may decide to call a bell to run in, then let a whole course be rung before again calling them to run in. Once they’ve grasped running in/out you could call a touch randomly requiring their bell to do either piece of work interspersed with plain leads. This clearly requires a longer piece of ringing but, as long as you’ve planned for it, why not? Whoever said Plain Bob Doubles touches can’t exceed 120 changes?

Having dealt with running in/out, move on to considering the work of the other two bells who will repeat a short course of work, i.e. make the bob or long fifths. This is a good time to visit the theory with a reminder that all “work” occurs at the treble’s lead (one ringer told me that before she learned to ring inside she thought “bob” was a reminder to the treble to lead!) The theory will reveal why 2 and 3 hunt through the lead end and “do it next time”, whereas after a bell makes the bob it rings long fifths next. The concept of “place bell” can be usefully established and is good preparation for more advanced methods in the future.

Using “Bayles” or its close relation “Thingummy” – techniques also known as “Groundhog Day”

These are simply ways to start ringing Plain Bob Doubles and then at any point have the band repeat a specific lead over and over in isolation before either calling “stand” or issuing a call that tells the band to drop back into Plain Bob Doubles. A key issue here is ensuring that communication is clear. Some towers use it a lot but in some places there may be hesitance, often due to long-standing ringers being unfamiliar with it or reluctant to try “new-fangled ideas”. If it’s not part of the tower’s regular diet rehearse it first with a band who can ring Plain Bob Doubles and then ask someone to give their rope to the new ringer.

Resource Tips

You can find details of these and other “stepping stone” methods in the Methods Toolboxes.

Pip Penney

4. Looking after the band

Keep your ringers ringing

Your new ringer has learned to handle a bell and is now ready to ring rounds with others.The next stage of their learning experience will be very different. The teacher and new ringer have been working together intensively on a one to one basis, with the ringer at the centre of the teacher’s attention. Now the learning curve will flatten out. As the ringer progresses towards elementary change ringing they will have to wait their turn to ring on practice nights and progress often seems hard to achieve, leading to frustration. Interest and motivation often wane...

Keep ALL your ringers ringing

Every activity wants to keep the numbers of participants as high as possible and keep people involved for as long as possible. Ringing is no exception – we want to retain the ringers we recruit. What is the best way of retaining and motivating developing ringers?

Are we giving our ringers what they really, really want?

Do our ringers come ringing purely for the pleasure of the ringing itself? The likelihood is that most of them do not. You might think that it will depend on the standard of the ringing they are involved in but it is not that straightforward.

What type of ringers do you teach?

Specific types of ringers need different coaching approaches. Accepting the fact that as a ringing teacher you are unlikely to be able to become an expert coach for all of the different groups, how do you cater for the various coaching requirements of different types of ringers?

Improving retention and extending performance

The latest research shows that more people stay actively involved if their training changes with the developmental stage they are at, and the different rates of progress ringers make. This creates a larger pool of people who remain actively involved, and from whom high-end performers and experts can emerge over an extended period.

Why do ringers lapse?

Alison Smedley has carried out a piece of action research as part of a BA course in Charity and Social Enterprise Management with Anglia Ruskin University in which she identified bellringing as: 'A voluntary activity which seemed to have a particular problem with retention of its participants is that of bell ringing'.

4.1. Keep your ringers ringing

How to take the step from novice to improver

The new ringer has learned to handle a bell and is now ready to ring rounds with others. The next stage of their learning experience will be very different. The teacher and new ringer have been working together intensively on a one to one basis. The new ringer has been at the centre of the teacher’s attention.

Now the learning curve will flatten out. As the ringer progresses towards elementary change ringing they will have to wait their turn to ring on practice nights. Progress often seems hard to achieve, which can lead to frustration. Interest and motivation often wane.

As the keen new ringer or novice moves on to become a developing ringer or improver the teacher faces a big challenge in keeping the ringer interested and motivated. In any activity this is a time when participants drop out.

Developing self awareness in our ringers

A good teacher must be aware of these potential problems and encourage the developing ringer to become self aware, both of bell handling style and listening, so that good striking can be developed independently even if the teacher is not present. A simulator is an excellent way to help a developing ringer tune into intrinsic feedback and help improve listening skills. The ringer can start by ringing the tenor behind. As the skill develops the ringer can ring an inside bell in rounds and over time can move on to ringing Plain Hunt, methods and larger numbers of bells.

Teachers should help the developing ringer to use his or her own internal (intrinsic) feedback through the ears to improve listening skills and help improve striking.

In the tower, listening and striking can be developed on as few as 3 or 4 bells. The advantage of using low numbers of bells is that few helpers are required and it is easy to distinguish the sound of one bell. Arranging practices for the obvious benefit of one or two developing ringers helps to reinforce the feeling that they are valued as individuals, which is in itself motivating.

Kaleidoscope sequences can be used such as Treble Bob Hunt or Cambridge front work can be used to develop the skill of moving the bell with accuracy. These training sessions have the added advantage of adding variety to the developing ringers’ experience that will help to maintain interest.

Improving understanding

A ringer’s curiosity can be satisfied by understanding the background to ringing. Theory should be taught to promote understanding and maintain interest. During later stages this accumulation of understanding will assist in the learning of more advanced methods. At each stage, teachers should ensure the ringer’s practical skills are under-pinned by theoretical knowledge.

Opportunity to assist with maintenance tasks in the belfry and through this gain an understanding of the mechanics of bells may be of interest to some ringers and help them to feel more involved.