Advanced Call Change Toolbox

| Site: | ART Online |

| Course: | Advanced Call Change Toolbox |

| Book: | Advanced Call Change Toolbox |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 23 November 2024, 11:54 AM |

Table of contents

- 1. What is Devon style ringing?

- 2. All about leading

- 3. Ringing with others

- 4. Ropesight, listening and striking

- 5. Ringing heavier bells

- 6. Ringing lighter bells

- 7. Kaleidoscope Exercises

- 8. Raising and lowering in peal

- 9. Simple Call Changes

- 10. Calling Call Changes

- 11. Advanced Call Change sequences

- 12. Jump Changes

1. What is Devon style ringing?

A style of full-circle ringing traditionally rung in Devon and Cornwall. It is characterised by:

- Call change ringing of set, named Call Change sequences

- Calls are rapid

- Closed or cartwheel leads

- Sequences rung below the balance and ringing is quick

- Performances start with a raise and end with a fall

- The raise starts with, and the fall ends with, all bells starting and stopping at one (no fade in or catching and stopping)

It has a reputation for excellent striking and a high quality raise and lower.

If you decide to join a practice in Devon or Cornwall, you'll be made very welcome, but be prepared for Devon style ringing!

Ringing differently in Devon

Listen to the Fun with Bells podcast interview with Ryan Trout.

Fun with Bells interview with Ryan Trout

Devon style ringing

In this case, a video is truly worth a thousand words.

2. All about leading

When a bell is ringing in the first place of a rowit is said to be leading. It does not follow a bell in the same way that the other bells do, and striking it well requires practice.

You can learn about leading from watching and listening to the treble in rounds:

- Stand behind the treble.

- Watch how it follows the tenor at the opposite stroke.

- Listen to the handstroke gap – is it open or closed?

There are two types of leading – closed or open. Generally method ringing bands ring with open handstroke leads, whilst those from the Devon Call Change tradition ring with closed handstroke leads.

Open handstroke leads

Listen to these simulated rounds and you'll hear a one-beat gap after every twelve blows. This is the handstroke gap.

The backstroke row follows on immediately after the handstroke row. However before the treble leads again at handstroke there is a gap or space of one blow. This is known as the handstroke gap or lead.

The bell that is leading cannot look at and follow the bell in front of it in the row. Instead it must lead by following the last rope to come down on the opposite stroke. When leading at handstroke the bell follows the backstroke of the last rope down and when leading at backstroke the bell follows the handstroke of the last rope down. To start with your teacher will usually ensure that this is the tenor.

Closed handstroke leads

Now listen to these simulated rounds where there isn't a gap after every twelve blows. This type of leading is known as a closed handstroke lead, or cartwheeling.

Video resources

What exactly is good striking? Watch this video to hear some examples of good striking and listen for errors. The handstroke gap is also explained and demonstrated.

3. Ringing with others

Rounds

Once you have learned to handle a bell you will be ready to ring rounds with other ringers. You will be aiming to ring with even, rhythmic striking without any “clips” or “gaps”.

In rounds the bells are rung in a sequence of descending notes starting with the treble and finishing with the tenor in a row [a sequence in which every bell strikes once]. The gaps between the bells should all sound even:

1 2 3 4 5 6

In rounds the 1 [treble] rings first [or leads]. The 6 [tenor] rings last, is “ringing behind” or is “covering”. The 3 is ringing in 3rd place [a place is the position in which the bell sounds or strikes in the row]. The term 'tenor' is applied to the bell of deepest tone in any peal of bells but is also used to denote the last bell in the set being rung. For example, many 12 bell towers have a second number two bell tuned to a semitone higher than the normal bell. This allows for a light 8 to be rung on the front 8 of the 12 with this semitone bell instead of the normal number 2. Other combinations are possible in towers with more bells.

One aspect of ringing rounds that is variable is the gap between successive bells as the number of bells increases. For example, the gap between the 2nd and 3rd bell when ringing 12 is much smaller than if the same two bells were ringing rounds on 6.

Bell control and keeping in the right place in rounds

To ring rounds successfully you need to be able to change the speed of your ringing at both handstroke and backstroke. At first your teacher will tell you to ring quicker or slower to keep in time with the other ringers. Over time you will develop your own listening skills so that you can do this yourself.

If you need to ring more quickly

You will need to ring below the balance so that the bell moves through a smaller arc. Slow or check the sally or backstroke so the bell does not rise as high. You may need to:

- Check the sally and don’t let it rise so high at handstroke.

- Take some rope in (shorten the tail-end) at backstroke.

- Put more weight on the stroke to keep the bell up after you have checked the stroke.

If you need to ring more slowly

You need to ring at the balance so that the bell moves through a complete arc. Let the sally or backstroke rise to (or nearer) the balance. You may need to:

- Put more weight into the previous stroke.

- Let the sally rise a little higher at handstroke.

- Let some rope out (lengthen the tail-end).

Ringing with others for the first time

When all the ringers have taken hold of their ropes the treble ringer will say “Look to”, or “Look to the treble”. This is a warning that ringing is about to start. You should then put some tension on the sally to pull the bell off the stay towards the point of balance in preparation for an accurate pull off.

The treble ringer will then say “Treble’s going” (and will check that the ringers have looked to) followed by “She’s gone” as they pull the treble off. You should then pull off your bell in rounds immediately after the bell you are following.

To stop the ringing the conductor will call “Stand” or “Stand next time” when the treble is ringing at handstroke. You should ring that handstroke, the following backstroke and set the bell on the following handstroke.

Bell control exercises

The Method Toolboxes contain plenty of interesting and challenging exercises for improving bell control. If you're a ringing teacher have a look at the Method Toolboxes for teachers.

4. Ropesight, listening and striking

Once you start to ring your bell with others you will learn how to put your bell in the right place. You need to know where in the row to ring your bell and develop the techniques to place it accurately in this place:

- Listening – you need to be able to hear your bell in the row.

- Ropesight – you need to be able to see which bell you are going to follow next in the row.

- Rhythm – you need to develop a feeling for the rhythm of the row.

None of these skills can be learnt by reading a book and they develop over time. Some ringers find them easier to acquire than others. Like many skills in ringing they are best learned in small stages.

Your goal is to be able to produce rows that are evenly spaced with no “clips” or “gaps”. This is good striking.

Listening

You need to be able to hear your bell when ringing rounds. That is you should be able to pick out the bell you are ringing and where it is sounding in the row. You should listen to the rounds and to the position [place] your bell is sounding in and adjust it to ensure an even rhythm. You should count the place it is sounding in as you ring.

It is easier to hear your bell when ringing rounds as the sound is so simple and familiar. Moving on to ringing changes before you can hear your bell strike in rounds will make it very difficult for you to learn to hear your bell later on.

If you are not sure whether it is your bell which is sounding too close to another bell or is leaving a gap you can use a technique called “crash and gap”. You ring your bell closer to or further from the one in front until you hear a crash or a gap. This helps you identify which bell is yours.

Some towers have simulators; the sound is generated electronically and sounds in the ringing room through speakers. The bells are tied and no sound is heard outside. Using a simulator will help develop your listening skills and give feedback on your progress.

Ropesight

Ropesight is the ability to see in which position your rope is moving amongst the other ropes. You will learn to see which bell you are following and find which bell to follow next from the movement of the ropes. This video resource describes ropesight using a dynamic diagram of Plain Hunt on five bells. You can then watch this being rung in a tower.

What is ropesight?

Ropesight takes time to develop and you will get better as your ringing progresses. Some ringers find it easier to acquire than others. Like many skills in ringing it is best learned in small stages.

The easiest way to start developing ropesight is by staying in the same place in the row – in call changes, kaleidoscope ringing or covering. You may find it easier initially to see the bells being followed when sitting out.

Covering allows you to develop ropesight by seeing bells change places below you. You will have started to do this when learning to ring call changes when two bells change places below you. You may not have been ringing the tenor. As you ring the tenor count the changes below you sounding your bell in your head in the last place of the change.

1 2 3 4 5 6

Again, if your tower has a simulator your teacher may give you an opportunity to ring the tenor on the simulator. This is good practice for developing rhythm on 6 bells.

Once you can ring the tenor rhythmically to rounds and call changes your teacher may move you on to covering to Plain Hunt and other methods.

You cannot learn ropesight by learning the numbers of the bells that you follow. When ringing the treble to methods (the next step) the treble rings the same line as in Plain Hunt but the order of the bells you strike over will vary in ways that you won’t be able to learn.

Watch this touch of Plain Bob Doubles, stood behind the treble and try and work out which bell the treble must follow next. The video plays through twice, once at full speed, once slowed down. This video was created for the purposes of developing ropesight.

Rhythm and striking

Ringing good rounds will help you develop a sense of feel for the rhythm of the bells as will counting the bells as they sound. Always put an emphasis on the place you are ringing in. For example if you are ringing the 4 in rounds you would say to yourself:

1 2 3 4 5 6

Using words (sentences) may help you to get the feeling of the rhythm. Choose a sentence which has twice the number of syllables than the number of bells being rung. For instance on six you could choose “We all love fish and chips, I want some for my tea” or “I want to go to town, to buy some fish and chips”.

When you move on to Plain Hunt, your first aim is to learn the “feeling” of moving slowly up to the back, lying for two blows, ringing more quickly down to the front and then leading. After practice your body will learn this “feeling” or rhythm and know automatically when to change speed and how much to pull or check to make the bell ring at the required speed and strike in the right place.

Listening to your ringing will help you hear if there are gaps or clashes and then to adjust your blows to make the sound even and rhythmic. The hardest part to master is when the speed of ringing changes.

To develop the physical skill of hunting, to begin with you need to know which bells to follow. However, you should always count the place your bell is in the row rather than say the number of the bell you are following in your head.

You can practise counting your place when you are not ringing by watching another ringer; it is sometimes surprisingly difficult to count backwards when coming down to the lead.

Changing the speed of your bell

Once you can hear your bell, you can alter your ringing until the spaces between the bells all sound evenly.

If you need to ring more quickly

You need to ring below the balance so that the bell moves through a smaller arc. Slow or check the sally or backstroke so the bell does not rise as high. You may need to:

- Check the sally and don’t let it rise so high at handstroke.

- Take some rope in (shorten the tail-end) at backstroke.

- Put more weight on the stroke to keep the bell up after you have checked the stroke.

If you need to ring more slowly

You need to ring at the balance so that the bell moves though a complete arc. Let the sally or backstroke rise to (or nearer) the balance. You may need to:

- Put more weight into the previous stroke.

- Let the sally rise a little higher at handstroke.

- Let some rope out (lengthen the tail-end).

5. Ringing heavier bells

The LtR Advanced Call Change scheme requires you to ring call changes on different bells, including heavier ones. Some ringers have the misconception that ringing a heavy bell takes great physical strength, but it is in fact more dependent on technique. Plenty of slightly built ringers can be excellent tenor ringers because their bell handling is efficient. If you are invited to ring in rounds and call changes, ask whether it’s possible to ring the tenor so that you can gain experience at ringing a larger, slower bell.

If you are learning to ring at a tower with quite large bells, you may need to gain confidence ringing the back bells, as they turn more slowly than the lighter bells at the front. As pulling off in rounds requires more forward planning with a larger bell, it’s worth spending some time polishing this skill before embarking on change ringing. If the tenor at your tower is rung standing on a box this could also take some getting used to. If you’ve only rung lighter bells before, you may wish to build up to ringing progressively larger bells.

This excellent video from Julia Cater at the St Martin’s Guild has plenty of useful tips about ringing larger bells.

6. Ringing lighter bells

One of the 50 Ringing Things is to Ring on a bell lighter than 3 cwt (152 kg). My home tower is a six with the front three less than 3 cwt, so we do get the occasional visitor who comes along to collect a thing. What do I tell them before they catch hold?

There is one component of a bell mechanism which doesn’t weigh ever so much, but the weight of which starts to matter more and more as the weight of the bell gets less and less. This is because the weight of this bit doesn’t reduce much as we go from a heavy bell to a lighter one. Perhaps surprisingly, this is the rope itself!

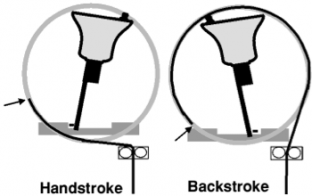

Think about what happens to the rope as we ring a bell. The image may help you to visualise it.

When you pull the sally at handstroke the wheel turns and the rope comes down, then it goes back up and is wound right around the wheel ready for the backstroke. But, because the sally has risen to a higher point now, more rope is wound onto the wheel than before – and you need to have provided enough energy to add to the momentum of the bell to get all that rope up there. With a light bell there isn’t much momentum, so you have to pull the handstroke relatively firmly to get the rope to do that. At backstroke, however, the weight of the rope itself will help you to turn the bell, and the additional energy this provides will easily lift the shorter length of rope back up again. If you’re ringing in a tower with a long draught the effect is even more obvious because a longer rope weighs more.

So here are some things to think about:

- Try to feel the point of balance, even though it’s less obvious than with a heavier bell

- At handstroke you will probably have to pull quite a bit more firmly than you expect, but start gently as you don’t want to endanger the stay

- Keep tension in the rope at backstroke, but try not to add any more energy – it probably won’t be needed

- Keep your arms high at both handstroke and backstroke, and accurately adjust the rope length, so as not to bump the stay

Another time when a difference is obvious is when raising or lowering a light bell in peal. When raising, it’s very easy to go up far too quickly, and lowering often catches people out because heavy bells have enough momentum to stay up without much work from the ringer. Whereas with a light bell you really have to work to keep the bell far enough up even as it’s coming down – you’ll probably find that you need to add energy at every stroke, even when you’re ringing one-handed. It also helps if you can make or release coils without thinking, so you can concentrate on accurately following the bell in front of you on every stroke.

One final point: one of the other things is to Ring on a Mini Ring with a tenor less than 1 cwt or 50 kg. What I’ve said here doesn’t really apply to a mini ring because they are engineered differently, so if you want to collect that thing as well you’ll need to seek further advice before you have a go at that.

To find out more, why don't you read the article Does size matter? from The Ringing World, available at cccbr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/200205.pdf.

7. Kaleidoscope Exercises

What is kaleidoscope ringing?

Kaleidoscope ringing is a series of exercises made within two places. If you're following the LtR Advanced Call Change scheme you won't be required to practise dodging or making changes starting at backstroke.

Kaleidoscope ringing differs from call changes in two ways:

- You only move one place (up or down) from your starting position – the ropesight is easier.

- You continue making the change until told to stop – developing your bell control.

Short and long places

Places requires a bell to ring two or more blows in a single place. The simplest kaleidoscope exercises are:

- Long places – four blows in one place, followed by four blows in either a place higher or lower in the row.

- Short places – two blows (one whole pull), rung in a single place, followed by two blows either a place higher or lower in the row.

Download and print a sheet of basic kaleidoscope works to use in the tower

Ringing your bell in the right place

Try to ring kaleidoscope exercises off as many bells as you can, with the proviso that you need to be able to control the bell to be able to position it in the right place in the row. You will have to change the position of your bell in the row, which requires you to ring your bell at three different speeds. Changes of place (whether up or down) need to be crisp – you should aim to move exactly one place in the row on just the one stroke.

How to change the speed of your bell

Ringing call changes will have taught you how to move you bell up and down one place, which will be good practise for striking long and short places successfully. When these basic manoeuvres have been mastered, you will move on to dodging. To dodge successfully you need to be able to change the speed of your ringing at both handstroke and backstroke. At first your teacher will tell you when to ring quicker or slower to strike your bell in the right place. However you will quickly be expected to do this yourself by using your listening skills.

Using kaleidoscope exercises

Having learnt and successfully rung some of the easier kaleidoscope exercises you can invent your own more complex sequences.

Longer kaleidoscope exercises can also be useful for ringers who want to practise pieces of work found later on in method ringing.

Kaleidoscope variations

There are a couple of named kaleidoscope exercises that will test you and your band. They can be rung for services and weddings, adding variety, whilst sounding interesting.

8. Raising and lowering in peal

Raising and lowering in peal requires practice. Lots of it! It's not an easy topic to summarise in a number of bullet points, so instead we've included a YouTube recording of a Graham Nabb workshop and you can buy the Raising and Lowering DVD which covers the theory and practice from raising and lowering a single bell and in peal through to leading up and down.

A raise is often the first part of a public performance and a lower the last, so make it sound great!

9. Simple Call Changes

What are call changes?

A call change is when the conductor calls for two adjacent bells in a row to swap places. For example from rounds (1 2 3 4 5 6) the conductor's call "3 to 4" will swap the two identified bells so that the order of the bells becomes (1 2 4 3 5 6):

(1 2 3 4 5 6) becomes (1 2 4 3 5 6)

In exactly the same way from this new row (1 2 4 3 5 6) the conductor's call "3 to 5" will swap the two identified bells so that the order of the bells becomes (1 2 4 5 3 6):

(1 2 4 3 5 6) becomes (1 2 4 5 3 6)

A more detailed explaination is given in this YouTube video:

Calling up, calling down and calling by place

There are three ways of calling Call Changes. Make sure everyone knows which method is being used, before you start ringing. The three different calls below all lead to the same change:

| Calling up | 1 2 3 4 5 6 | “3 to 4” | 1 2 4 3 5 6 |

| Calling down | 1 2 3 4 5 6 | “4 to 2” | 1 2 4 3 5 6 |

| Calling by place in the rows | 1 2 3 4 5 6 | “3rds place bell follow 4ths place bell” | 1 2 4 3 5 6 |

Call Change jargon

Call Changes bring with them a whole new set of jargon. Why not test yourself with this Call Change Jargon quiz to make sure you really do know what others are talking about?

Ringing your bell in the right place

Try to ring call changes off as many bells as you can, with the proviso that you need to be able to control the bell to be able to position it in the right place in the row. This will be the first time that you will have had to change the position of your bell in the row, which requires you to ring your bell at three different speeds. This change of speed takes place at one stroke (usually handstroke).

How to change the speed of your bell

When you are called up you will need to hold up and ring slightly slower than in rounds for one blow:

- The conductor will call the change at handstroke.

- Put more weight on the backstroke before the change is made, in order to get more energy into the rope.

- At the handstroke in which the change is made, let the sally rise a little higher so that you ring after the bell you've moved over.

When you are are called down towards the front, you will need to ring slightly quicker than in rounds for one blow:

- The conductor will call the change at handstroke.

- At the handstroke in which the change is made, check or slow the sally so the bell does not rise as high. Put more weight on the handstroke to prevent the next backstroke from dropping.

When leading and lying ring at the same speed as in rounds. Remember the open handstroke lead – that is the little extra gap at the handstroke lead (equivalent to one blow).

Test yourself by trying the bell control and call change quiz.

Named changes

Some call changes have special names e.g. Queens or Whittingtons. We have compiled a list of named musical rows which are are known across the country, but be aware that there are one or two regional variations.

Learning aids

You can consolidate your understanding of the theory of call changes using these exercises and games:

- Call Changes – calling up (written exercises)

- Call Changes – calling down (written exercises)

- Call Changes quiz – calling up

- Call Changes quiz – calling down

- Call Changes – dominoes

- Call Changes – crossword

Beyond call changes

Video resource

The St Martin's Guild ring a call change sequence (between named musical rows) starting with raising the bells in peal and ending with a lower.

Supporting resources

If you want to learn more about ringing and calling call changes then try the Understanding Call Changes online course.

10. Calling Call Changes

This might well be your first opportunity to speak whilst ringing, which can be a lot harder than it sounds. Tips and exercises are given in the Understanding Call Changes online course. Remember to speak loudly, speak clearly and speak at the right time.

Starting to call

Calling changes re-arranges the bells into different positions, often with a particular order in mind so that they sound particularly musical. Although there are plenty of named call rows (such as Queens or Tittums), part of the fun of call changes is the conductor composing their own patterns, making up calls as they go along and returning the bells to rounds at the end.

You can start by calling the changes from outside the circle when you're not ringing a bell. Begin by keeping it simple, perhaps calling two bells to swap, then calling them back to their original positions. When you call whilst ringing, ring a bell that doesn't move much and only move one bell one or two places and back again. You'll know you're an expert when other members of the band randomly call changes and you can then call them back to rounds. Some very experienced ringers have difficulty doing that!

If you need help working out how to call to named rows, the following downloads will help:

How and when to call

When calling anything in the tower, it’s important to speak clearly and above the sound of the bells, without shouting so loudly that you deafen the other ringers.

Calls should be made just as the leading bell is pulling off at handstroke. If a call is too late, some of the bells might have already pulled their backstroke, so may not be prepared, or able, to make the change at the next handstroke.

First steps

To start with, try calling changes whilst you are not ringing yourself. Stand outside the circle, and have a plan of which bells you are going to swap. Make one call, observe how it takes effect, how it sounds once it has settled, then when you’re ready, call the bells back to their original position. Repeat this, changing a few more bells, then reversing the changes. When you are completely confident with calling simple changes, progress to calling changes whilst ringing a bell yourself. To start with, you may wish to call other bells to change so that you aren’t affected yourself.

As with all skills in ringing, the most successful callers are those who spent time practising. Even if you stick to very straightforward changes, these will be ideal for most service ringing or weddings.

Planning ahead

If you’re aiming for a particular named call row, it may help to do some homework in advance by writing out the calls. Memorise a few calls to get the bells into their final order, then back to rounds. Practise calling them out loud before you get to the tower, and if it helps, try calling when you’re standing out and not ringing before you take part yourself.

If aiming for Queens, you could plan it as follows:

- Bell position at call 123456

- Call ‘2 to 3’ if calling up, (or ‘3 to 1’ if calling down) Bell position after call 132456

- Call ‘4 to 5’ if calling up, (or ‘5 to 2’ if calling down) Bell position after call 132546

- Call ‘2 to 5’ if calling up, (or ‘4 to 2’ if calling down) Bell position after call (Queens) 135246

To return the order to rounds, simply work backward:

- Bell position at call 135246

- Call ‘5 to 2’ if calling up, (or ‘4 to 5’ if calling down) Bell position after call 132546

- Call ‘5 to 4’ if calling up, (or ‘4 to 2’ if calling down) Bell position after call 132456

- Call ‘3 to 2’ if calling up, (or ‘2 to 1’ if calling down) Bell position after call (Rounds) 123456

Allow the band to ring rounds for a little while before calling ‘stand’, again just after the treble has led at handstroke, so that everyone has time to prepare for this to take effect at the following handstroke.

As you progress, you should develop more awareness of the position of each bell and be able to start making up changes as you go along, then returning the bells to rounds. Many callers enjoy creating musical sequences of ringing.

You’re in charge

Even if you are quite new to calling, if you’re the designated conductor, you have the responsibility to stop the ringing if people get lost or the striking becomes too choppy.

As you gain experience with calling, you may be able to offer helpful advice if ringers make mistakes, but if things become too muddled and you’re not sure how to help, calling ‘rounds please’ and starting again is a perfectly acceptable option.

11. Advanced Call Change sequences

Having tried a number of call change sequences, you can move on to longer sequences which follow standard calling patterns. The whole band can learn the sequence, in a similar way to which the whole band must learn a method to ring it. Learn the pattern, not the calls. The aim is for calls to be made quickly (target – every handstroke) so that the sequence is completed in a reasonable period of time and making it easier for the conductor to remember the sequence.

Click on a sequence title to download a resource with each change and call written out and a more detailed account of the calling pattern.

The twenty all over

- Every bell is called into fifth place in turn.

Up the garden path

- Start and finish from an agreed musical row.

- Call each bell from the lead to the back, in turn – i.e. start with the 1, then the 3, 5, 4 and finally the 2.

The resource shows the pattern starting from rounds but you can try the same exercise starting from different musical rows e.g. Queens, Whittingtons or Tittums.

Forty-eight changes

- Think of bells 4 and 5 as whole hunt bells and bells 1, 2 and 3 as extreme bells.

- Alternately call the 5 and then the 4 to lead.

- Each time one of the whole hunt bells is leading swap either the first two or the second two extreme bells. If the 5 is leading swap the first two extreme bells. If the 4 is leading swap the second two.

- When the extreme bells are in the order abc then a and b are the first two, and b and c are the second two.

Sixty on thirds

- Call to Queens.

- Call the treble to 5ths place.

- Move the bell A (the bell that is leading) up one place.

- Call the treble to lead. Move bell A up one place.

- Call the treble to 5ths place. Move bell A up one place.

- Call the treble to lead. Bell A will now be in fifth place.

- Repeat the above sequence. Once bell A has reached fifth place, the bell that is leading becomes bell A.

- Once the sequence has been repeated 4 times in total, the bells will have come back into Queens.

- Call to Rounds.

These are the changes for the Devon competition peal, as specified by the Devon Association of Ringers.

Devon 8-bell competition piece

- Call to Queens.

- Call each bell 1 to 7 from the lead to 7ths place.

- Once the all the bells have been called from lead to 7ths place, the bells will have come back into Queens.

- Call to Rounds.

Video resource

This video footage shows Shaugh Prior bellringers ringing at South Brent on 10 June 2014. This was the teams last practise ring prior to the Devon Association of Ringers 2014 6-bell final held at Sampford Courtenay on Sat 14 June. The piece consists of: Rise, "Sixty-on-Thirds" and Lower.

12. Jump Changes

Jump Changes teach bell control, listening and awareness of a bell's position in the row. Only when these skills are well developed can clean, accurate changes between rows be had. Jump Changes are often rung at weddings and for church services as they revolve around musical rows that the public recognise and like.

Simple Jump Changes

Simple Jump Changes requires you to jump between rounds and named, musical rows, e.g. Queens or Whittingtons. These changes are recognised across the country, but beware as there are one or two regional variations. You will need to know a small number of these named changes before you can ring jump changes. The most popular are:

- Queens: 1 3 5 2 4 6

- Tittums: 1 4 2 5 3 6

- Whittingtons: 1 2 5 3 4 6

- Kings: 5 3 1 2 4 6

We have compiled a list of named musical rows which are are known across the country, but be aware that there are one or two regional variations.

Changes are made on the conductor’s command. From rounds the conductor calls “Queens” or any other chosen musical row. At the next handstroke the bells must ring in the “Queens” sequence. Your aim is to make the change crisply and accurately at the following handstroke. When you first start ringing jump changes you might find that:

- The handstroke change is ragged as people struggle with moving their bell more than one place.

- The handstroke change is slow as people rely too much on ropesight to get their bell in the right place.

- The change takes a few rows to settle down.

This is perfectly normal, and the conductor will give you feedback on how to improve.

Ringing your bell in the right place

Try to ring jump call changes off as many bells as you can, with the proviso that you need to be able to control the bell to be able to position it in the right place in the row – you need to be able to ring your bell at three different speeds.

Advanced Jump Changes

The changes are called like conventional call changes (e.g. "5 to 4") but bells are called to move more than one place away from their position in a single call. On higher numbers, the move may be many places and the higher the number of bells the bigger the jumps. These changes evolved from a need to reduce the number of calls in sequences on higher numbers, which can take a very long time on 12 or 16.

The big jumps require the speed of your bell to be changed in exactly the same way as for simple call changes. Thinking of bell control and changing the speed of your bell:

- The bell that is being asked to 'jump' needs to be held on the balance for some time before ringing after the nominated bell.

- All the bells between the bell that is “jumping” towards the back of the row and the bell that it was originally following need to ring quicker for one blow as the row shifts down.

For example: in the change below, the call is "2 to 5", and the bells 3, 4 and 5 will need to ring quicker for one blow to allow 2 to take its place in fifth place, following the 5.

(1 2 3 4 5 6) becomes (1 3 4 5 2 6)

Calling Jump Changes

As the conductor you need to call from rounds the to a named musical row, e.g. Queens. Make the call just after the treble pulls off a handstroke and the change takes effect at the next handstroke. As your band gets more accomplished you can add complexity and variety by:

- Picking one musical row and alternating between that and rounds.

- Repeating the exercise using another musical rows besides rounds.

- Increasing the difficulty by jumping from one musical row to another e.g. Queens, Tittums, Whittingtons, and back to rounds.

Teaching tip

Share the sequences with everyone in the band before you ring. If people know what call is coming next they will spend less mental energy worrying whether the next call affects them, and can concentrate more on their striking. Here are some Advanced Jump Change sequences that you can share with the rest of the band.

Jump Changes on YouTube

There are very few examples of jump changes on YouTube. Here's one of jump changes being rung on twelve bells by the St. Martin's Guild, Birmingham. The sequence cycles from Rounds to Queens to Kings and back to Rounds in only 15 calls.

You may wish to download a listing of the jump changes to see the calling pattern used. The calling is not random!