Method Toolboxes for teachers

| Site: | ART Online |

| Course: | Method Toolboxes |

| Book: | Method Toolboxes for teachers |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 4 December 2024, 8:28 AM |

1. Introduction

These resources have been developed to give you lots of ideas and exercises for the teaching of foundation skills and method ringing. They take you from teaching someone how to ring well struck rounds to the ringing and calling of methods. They cover all the skills and knowledge that a developing ringer needs to acquire in order to become a competent and confident bellringer.

Use this workbook in conjunction with Method Toolboxes for Ringers and share those resources with your learners.

People are comfortable learning things in different ways, so there's lots of videos as well as written and visual explanations included in the toolboxes. Finally, if you have access to a simulator take advantage of it – it's a great way for ringers to practise what they've learnt.

2. Foundation Skills Toolbox

Good foundation skills are the bedrock of a ringer's development. These are the skills which will allow a ringer to progress with their ringing:

- Bell control

- Listening

- Rhythm and striking

- Ropesight

- Understanding the theory

The first four of these cannot be learnt from a book; they are learnt through practice and experience. The more time spent ringing, the more these skills develop. The better the quality of the ringing someone participates in, the more quickly these skills develop.

This chapter explains the theory behind the foundation skills and describes exercises that you might perform with your students to help develop these skills.

2.1. Teaching rounds

Once a ringer has learned to handle a bell they will be ready to ring rounds with other ringers. The aim is for them to ring with even, rhythmic striking without any 'clips' or 'gaps'.

Introducing the jargon

Introduce the ringer to the jargon associated with the pull off. If this is overlooked they quite often see it as an archaic phrase, rather than three necessary instructions, which can sometimes result in chaotic pull offs. Not a good start to a performance.

“Look to”, or “Look to the treble” is a warning that ringing is about to start. They should be advised to put some tension on the sally to pull the bell off the stay towards the point of balance in preparation for an accurate pull off.

“Treble’s going” will be followed by the treble ringer visually checking that all ringers have looked to.

“She’s gone” is said as the treble is pulled off. The student should pull off their bell in rounds immediately after the bell they are following.

Similarly at the end, to stop the ringing the conductor will call “Stand” or “Stand next time” when the treble is ringing at handstroke. The student should know that they must ring that handstroke, the following backstroke and be prepared to set the bell on the following handstroke.

What does good rounds sound like?

Particularly if you're a band with a number of ringers all learning together, it's a good idea to show people what they're aiming for. Visiting another tower with an experienced band can be an inspirational experience, particularly if that band is prepared to ring well struck rounds with each learner in turn. Alternatively, there are loads of YouTube videos to choose from and share with your band. Here's an example on 8 bells:

Working towards well struck rounds

To ring well struck rounds requires practice and the striking will slowly develop as the foundation skills are honed. The five foundation skills are:

- Bell control

- Listening

- Rhythm and striking

- Ropesight

- Understanding the theory (in this case this is the theory of leading)

Ideas and exercises for teaching the five foundation skills can be found in the following sub-chapters.

2.2. Teaching leading

Leading is a skill which relies on listening, timing, bell control and some ropesight, so it may be something to teach once a ringer has already begun to develop these skills and can reliably place their bell accurately when moving in basic call changes.

The theory of leading

When a bell is ringing in the first place of a change it is said to be leading. It does not follow a bell in the same way that the other bells do, and striking it well requires practice.

You can start teaching someone about leading by asking them to watch and listen to the treble in rounds:

- Stand behind the treble.

- Watch how it follows the tenor at the opposite stroke.

- Listen to the handstroke gap – is it open or closed?

Closed or open leads?

There are two types of leading – closed or open. Generally method ringing bands ring with open handstroke leads, whilst those from the Devon Call Change tradition ring with closed handstroke leads.

The whole band must decide whether it is going to ring with closed or open handstroke leads. It is recommended that the two types of leading aren't mixed.

The rhythm of open leads

If you don’t have an experienced band to demonstrate, it can be helpful to play a recording of well struck ringing and draw attention to the handstroke gap. You can find good examples on YouTube or in the Rounds and leading sub-chapter in the Method Toolboxes for ringers.

If you have a simulator or ringing software which plays samples of ringing, you can usually increase the length of a handstroke gap so that it becomes more apparent. It can also be instructive to remove the handstroke gap completely.

Clapping game

Ask ringers to stand in a circle, as they would for ringing. Start with everyone clapping together, one clap for each blow in rounds.

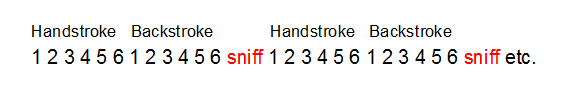

Immediately after the last backstroke clap, there is a pause (handstroke gap) before the next round starts. At this pause, the ringers should all open their hands wide to illustrate their gap for one blow or sniff, then start clapping the next round.

Go round several times until everyone has the rhythm, counting the blows in rounds and leaving the gap. Expect laughter every time one person forgets to leave the gap and claps instead.

Using handbells to teach leading

If you have a set of handbells (even toy handbells) these can be used to introduce leading in the same way.

Ring rounds with an experienced ringer taking the treble. Everyone rings a handstroke in rounds, then a backstroke in rounds. Where the handstroke gap comes, start by everyone saying the word ‘gap’ or ‘pause’ out loud. Once a rhythm has been established, take turns ringing the treble and leaving the gap.

Leading on tower bells

Teaching leading on tower bells does not necessarily mean the student has to ring the treble. If your tower has a light or flighty treble, pick a different bell for them to lead from to start with.

Watching and listening

Listen for the tenor bong and watch for the treble ringer’s hands leave the sally on the treble’s handstroke – with or without the handstroke gap.

Shadowing

Visually giving a hand to shadow and pointing out the relation to the tenor ringer’s hands then listen to adjust.

Alternate strokes

Start by ringing rounds, with bells on alternate strokes. This enables a new ringer to get used to following a bell on a different stroke, just as if using the tenor stroke as a visual aid to leading. This can be difficult and listening skills will also be developed.

Call changes

Ask an experienced ringer to take the treble but invite the learner to ring bell 2. Start ringing rounds steadily, then call the 2 into the lead. The treble ringer can maintain a steady rhythm in seconds place so that the remaining bells can follow them if the ringer who is leading loses the rhythm.

Once the rhythm of leading is steady, call them back to seconds place, then back into lead. Repeat this a few times for practice at being called in and out of the lead.

More ways to practise leading

To increase confidence and improve their bell handling skills, ringers could practise leading from different bells, including the treble and heavier bells.

Once leading at handstroke has been perfected, try a new challenge of leading at backstroke, going in and out of the lead.

Calling a new ringer up into fifths place, then back down again and into lead using successive handstrokes provides an opportunity for them to get used to the feel of moving down to lead – a step towards plain hunting.

2.3. Developing bell control

These ringing games are all based on rounds and are suitable for ringers of all abilities. They add interest, variety and fun to practices whilst helping developing skills such as leading, bell control, listening and ringing by rhythm. Download the Rounds Games cribsheet to use at your practice.

Aim for crisp, accurate rounds and be prepared to give lots of bell handling advice along the way.

Round Games

Rounds on 6 move right

This is an exercise in bell control. Ringing light and heavy bells requires specific, different techniques and acquiring the skill for both will make for better bell handling technique overall and increase versatility. Every member of the band should aim to be competent and comfortable ringing anywhere in the circle.

Ring short bursts of rounds concentrating on striking and listening. When the rounds are settled, stand, and everyone should move to ring the bell on their immediate right (which is safer than moving to the left – the jump from the weight of the treble to the heavier tenor carries less risk than jumping from the tenor to the treble). Less experienced ringers should start by ringing one of the middle bells.

Whole pull and stand

An exercise in anticipating the pull off and standing the bell.

The band rings rounds for one whole pull, after which everyone stands except the tenor, which rings for one whole pull on its own, before the rest of the band joins in again. This is repeated. A variation on this develops the ability to stand at will. Ask one of the ringers to pick a number between 1 and 10, or roll a dice. Ringers must ring rounds, count and stand on the stroke chosen. Repeat with random choices. If you get the impression people are avoiding standing at backstroke, ask a question which gives you the answer you are looking for.

Switch-a-roo

An exercise in bell control.

The band rings rounds until Switch-a-roo is called, when it switches to ringing back rounds the following handstroke. At the second call of Switch-a-roo the band reverts to ringing rounds again. Look for a clean change and discuss how the band might achieve this (light vs. heavy bells). Aim to switch every whole pull, once technique improves. Put your least experienced ringers in the middle as the speed changes are less dramatic. Increase the challenge by placing them further towards either end of the row as they get better.

Ring rounds facing outwards

This is a good exercise for developing listening skills and to practise ringing by rhythm.

Once steady rounds have been established, ringers take it in turns to face outwards and continue ringing rounds, striking in the right place. Who turns, when, should initially be controlled by the teacher. Once ringers are competent, they can take it in turns to nominate the next ringer to turn outwards. The challenge is for the band to maintain even striking. Demonstrate how and when to turn and give ringers an opportunity to practise turning on their own if they have not done it before.

Follow my leader

An exercise in adjusting speed.

Place the most experienced ringer on the treble and establish steady rounds. The treble ringer then starts to change the speed of their bell (faster or slower) and the rest of the band has to adjust their speed to keep the rounds regular and well struck. Ringers should use their listening skills but also watch the hands of the treble ringer. Teachers should look out for and help with any handling issues that crop up as ringers try to ring faster or slower.

Ringing rounds on alternate strokes

This is an exercise in leading and establishing rhythm. It is surprisingly tricky for more experienced ringers, so good fun on a practice night for mixed ability bands.

Odd numbered bells start ringing at handstroke, even numbered bells join in at backstroke. The aim is to get the rounds to sound right. Ringers will not be able to rely on watching the sally of the bell in front of them but will need to ring by rhythm and use their wider peripheral vision. For variety, repeat the exercise with odd numbered bells at backstroke and even numbered bells at handstroke.

Crash and gap

An exercise to help a ringer learn to hear their bell and how to make small speed adjustments to correct striking errors.

This exercise should be done with one, less experienced ringer ringing in between two ringers who can ring rounds steadily. Whilst ringing rounds, the less experienced ringer should start to alter the gap between their own bell and one of the neighbouring bells (up or down in the row) until they hear the bells clipping. They should then readjust until well struck rounds is achieved again.

Diminishing rounds or fading out

An exercise in listening, leading and adjusting speed.

The band starts by ringing rounds. To fade out from the front, the treble ringer stands their bell, leaving the 2 in the lead. After a few rounds, the 2 stands, so that the 3 is leading and so on, until the tenor is ringing by themselves. To fade out from the back, the bells stand one at a time from the tenor forwards. Fading out from the back doesn’t require all ringers to be able to lead, whilst fading out from the front requires everyone to be comfortable with leading.

Incremental rounds or fading in

A game that helps a new ringer hear which is ‘their’ bell and understand that the spacing of rounds varies with the numbers of bells.

Start with three bells ringing rounds with the new ringer on the middle bell. Check that they are able to hear which is their bell. Whilst ringing, another bell can join in with the rounds in fourth place. Allow the rounds to settle with the extra bell and check that the ringer can still hear which one is theirs. Keep adding bells, ensuring that they can still hear which one is theirs. When the band is competent at fading in and out, you can combine the two – fading out and then back in again.

Ring ‘o’ Roses

This exercise will increase confidence and safety with bell handling. Ringers should already be comfortable with ringing with one hand on the sally (as when raising a bell) before taking part in this game.

Ring rounds with one person not ringing. Each ringer has to pass control of their bell to the person who isn’t ringing. The tail end should be passed at the bottom of the stroke whilst the sally is being rung one handed. Demonstrate how to do this prior to starting the game for the first time.

Once the ringing bell has been passed fully to the new person, the ringer who is now standing out can take the rope from the next ringer in the circle. This can be done on just a few bells or round the whole circle.

Other foundation skills exercises

Bell handling advice

Be prepared to give lots of advice on bell handling, particularly how to successfully change the speed of the bell at both handstroke and backstroke. At first you will need to tell your student to ring quicker or slower to keep in time with the other ringers. Over time you should help them develop their own listening skills so that you can do this themself.

If the bell needs to ring more quickly

The bell needs to be rung below the balance so that it moves through a smaller arc. The sally needs to be slowed or checked at backstroke so the bell does not rise as high. The student may need to:

- Check the sally so that it doesn't rise so high at handstroke.

- Take some rope in (shorten the tail-end) at backstroke.

- Put more weight on the stroke to keep the bell up after they have checked the stroke.

If you bell needs to ring more slowly

The bell needs to be rung at the balance so that the bell moves through a complete arc. Let the sally or backstroke rise to (or nearer) the balance. The student may need to:

- Put more weight into the previous stroke.

- Let the sally rise a little higher at handstroke.

- Let some rope out (lengthen the tail-end).

2.4. Ropesight, listening and striking

Once your student can ring their bell with others they need to learn how to put their bell in the right place in the row. They need to know where in the row to ring their bell and develop the techniques to place it accurately in this place:

- Listening – they need to be able to hear their bell in the row.

- Ropesight – they need to be able to see which bell they are going to follow next in the row.

- Rhythm – they need to develop a feeling for the rhythm of the rows.

None of these skills can be learnt by reading a book and they develop over time. Some ringers find them easier to acquire than others. Like many skills in ringing they are best learned in small, incremental steps.

Your goal is to teach your ringer to produce rows that are evenly spaced with no “clips” or “gaps”.

Listening

Ringers are frequently told to listen to their bell. It comes more naturally to some than others. But what does listening to your bell actually mean? Basically, that a ringer can identify their bell when it is ringing amongst other bells and ensure it rings rhythmically amongst them. There are various exercises you can use to develop the listening processes that experienced ringers do subconsciously.

Ringers need to be able to know which place in the row they are ringing in. Right from the beginning you need to teach them to hear and count their place in the row.

Training can start by listening and practising using ringing software on their PC. Similar exercises can be performed using mobile phone apps or you can get your ringers to attend a listening & striking workshop. The use of a simulator is invaluable in developing listening skills. This can take place anytime and could be combined with on-going handling lessons.

Listening exercises

Throughout the following exercises remember to use feedback. If your ringer is not striking accurately they need to be told what is not right and how to correct it.

Ring facing outwards from the centre one at a time – the ringers turn around when the backstroke is up. When facing outwards they cannot see the rope they are following and must ring by ear. Call Changes can be used too if skills develop far enough. This exercise is not possible if the ringer needs a box.

Incremental rounds – start off with just three bells [the ringer is more likely to be able to hear their bell on low numbers] with the tenor ringing at normal rounds speed. Use the real tenor and any two other bells. Put the new ringer on the middle bell and confirm they can hear their bell. While ringing add a fourth bell and re-space to achieve good rounds. Continue adding bells for as long as the new ringer can still hear their

bell. They will not only learn to hear their bell but also realise that spacing changes on different numbers of bells.

Diminishing rounds – if a ringer cannot keep in rounds ask one bell to stand at a time until the ringer begins to identify their own bell. This exercise can also be used to practise changing the spacing on different numbers of bells.

'Crash and Gap' – start with the new ringer on the second of three bells. They experiment with striking by altering the gap between their own bell and one of the neighbouring bells until they hear a "crash". The crash enables the ringer to identify their own bell. The idea is to allow the ringer to "own" the sound of their own bell. The exercise can be repeated over time, on larger numbers of bells.

Ringing bells starting on alternate strokes – ring rounds with one bell on handstroke and the following one at backstroke etc. All the ringers must then work on getting the sound right. They should be asked to focus ahead seeing the bigger picture rather than following a particular bell. The strokes the various bells are on can be changed and the exercise repeated.

Ropesight

Ropesight is the ability to see in which position your rope is moving amongst the other ropes. It involves seeing which bell you are following and establishing which bell to follow next from the movement of the ropes.

Ropesight takes time to develop and an inexperienced ringer will get better as their ringing progresses. Some ringers find it easier to acquire than others. Like many skills in ringing it is best learned in small stages.

Ropesight cannot be learnt by memorising the numbers of the bells that are to be followed. Explain, that when ringing the treble to methods (often the next step in a student's ringing progression) the treble rings the same line as in Plain Hunt but the order of the bells they strike over will vary in ways that you won’t be able to learn.

At this stage in a ringer's development they can be introduced to some simple ropesight exercises. These involve ringing in the same place in a change whilst the bells underneath them change places.

Exercises to develop ropesight

Stand beside your ringer and explain that they will be remaining in the same place in the row, for example 4th place. Ensure they are counting their place. Explain that you are going to swap the positions of the bells underneath them by calling “2 follow 3” and that they will now still be ringing in 4th place but following the 2.

Once they have got the hang of this, call the 2 and 3 back into rounds. Repeat the exercise with no explanation to the ringer. If this goes well, call the bells 2 and 3 to change places every other whole pull and then every whole pull.

Once this is mastered, call 2 and 3 to continuously make places and finally get your ringer to follow them as they dodge. All this might only take one practice of a few minutes with a fast learner.

The next step might be to bring the treble up to 3rd place and repeat the above exercises. The ringer can then move on to covering to Plain Hunt on three bells. This exercise, designed for the ringer of the 4 to learn to cover, can also be used to give the ringers of bells 5 and 6 an opportunity to practise ringing rounds. Kaleidoscope exercises can be used to help develop the concept of ropesight.

Once the ringer can accurately cover to the above you can move them on to covering to Plain Hunt on more bells. For ringers who find covering to Plain Hunt on five bells difficult to learn, starting on small numbers of bells such as three or four may be useful.

Rhythm and striking

Ringing good rounds will help the ringer develop a sense of feel for the rhythm of the bells as will counting the bells as they sound. Encourage the ringer to always put an emphasis on the place they are ringing in. For example if they are ringing the 4 in rounds they would say to themselves:

1 2 3 4 5 6

Using words (sentences) may help you to get the feeling of the rhythm. Choose a sentence which has twice the number of syllables than the number of bells being rung. For instance on six you could choose “We all love fish and chips, I want some for my tea” or “I want to go to town, to buy some fish and chips”.

When you move on to Plain Hunt, you should emphasise the 'feeling' of moving slowly up to the back, lying for two blows, ringing more quickly down to the front and then leading. After practice their body will learn this “feeling” or rhythm and know automatically when to change speed and how much to pull or check to make the bell ring at the required speed and strike in the right place.

Listening to ringing (their own or others) will help a ringer hear if there are gaps or clashes. When ringing they need to be able to adjust their ringing to make the sound even and rhythmic. The hardest part to master is when the speed of ringing changes – moving in and out of the lead, or up to and away from the lie at the back.

To develop the physical skill of hunting, to begin with the student needs to know which bells to follow. However, they should always count the place their bell is in the row rather than say the number of the bell they are following in their head.

2.5. Call Change Toolbox

Call change ringing is what most new ringers move on to once they can ring rounds. Before ringing call changes a ringer should be able to:

- Ring rounds and stay in the correct place in the row.

- Be aware of where their bell is striking in the row and what place they are in.

- Hear when their bell is out of place and be able to adjust to get back into rounds.

- Ring quicker and slower.

- Understand why a change of speed is required to change place in the row.

Kaleidoscope Exercises can also be introduced at this stage of a ringer's development.

Teaching the theory of call changes

Learning aids

You can consolidate your understanding of the theory of call changes using these exercises and games:

- Call Change – calling up (written exercises)

- Call Change – calling down (written exercises)

- Call Change quiz – calling up

- Call Change quiz – calling down

- Call Change dominoes

- Call Change crossword

Putting it into action

Placing the band

Ensure you have a treble ringer who can lead well and a tenor ringer with a good sense of rhythm. Place competent ringers on either side of the ringer who is learning. For the very first call change it is easier for your ringer to work with the bells he is already looking towards and following in rounds. That is to say, get the ringer to move down a place out of rounds and up a place to get back into rounds. If you choose to do this, don't place the ringer on the 2, as, at this point in his ringing development they are unlikely to have learned how to lead.

The first call – what does your ringer need to know?

- That the call is made at the start of the handstroke row.

- That they will ring that handstroke followed by the backstroke.

- That the change of speed to get into the new place is made on the following handstroke.

- That the change of speed is for one blow only and then normal rounds speed is resumed.

Explain to your ringer that this whole pull warning gives them the opportunity to adjust the intervening backstroke to enable the bell to be moved into the new place more easily. They need to put less energy in when preparing to move down a place and ring the handstroke more quickly, and put more energy in to make the bell swing higher in preparation for holding up the following handstroke when moving up a place.

The ringer needs to understand what happens at a call, which bells are affected and in what way. For example if the call is 3 to 4:

- The 3 is has to hold up, ringing more slowly to follow the 4 in fourths place.

- The 4 is has to check in, ringing more quickly to follow the 2 in thirds place.

- The 5 stays in fifths place but now follows the 3 not the 4.

Using questions to check understanding

Using questions to check understanding ensures the ringer has processed the information. Ask your ringer, when your bell is called to move down [or up] does it have to ring more quickly or more slowly? This may seem obvious, but when asked this question many ringers are confused to start with:

- What place is your bell sounding in?

- Which bell are you following?

- Which bell is that following?

- Who is following you?

And when they have advanced a little:

- Which bell is leading?

- Which bell is behind.

And even…

- What is the order of the bells?

Following the call the teacher should…

- Observe how accurately the call was executed.

- Feedback to the ringer.

- Feedback is used to reinforce what is wanted – so tell them if their striking the change was accurate and if the following backstroke was accurate.

- Feedback is used to change and improve things – tell them where they were struggling and it was not sounding right.

- Give the ringer the information to improve performance at the next attempt – for example, “next time put a little less weight on your backstroke so that it is easier to get the following handstroke down into the new place”.

- Give the ringer opportunity to repeat the action.

- Give feedback again – improved? Still having problems?

- Repeat these two simple changes until the accuracy of the striking improves.

This whole process can then be repeated again by calling the ringer to move up a place, i.e. looking to their left to move up and to the right to move down again into rounds. Again repeat the feedback loop.

Moving beyond the basic moves

When a ringer can accurately move up and down a place and return to steady rounds, they are ready to move on to more complicated sequences. The ringer can be introduced to common sequences such as Queens (1 3 5 2 4 6), Tittums (1 4 2 5 3 6) or Whittingtons (1 5 3 2 4 6). Whilst ringing more complicated sequences the teacher should use questions such as:

- What place in the row is your bell sounding in?

- Which bell are you following?

- Which bell is that one following?

This process continues until you are certain that the ringer is always aware of their place in the row. Another ringer could be used to stand behind and ask these questions.

Reinforcing the sense of place

To help reinforce the sense of place in the row a ringer can be asked to call simple call changes, for example to call themself up and then back down a place or two places. A ringer who finds this exercise easy can move on to calling more complex sequences such as calling the bells into Queens or Tittums and back into rounds.

The use of exercises such as these can give you a good indication of the ringers who already have a good idea of where each bell is at each call.

The ringers can be asked to say the number of the place they are ringing in. Starting with the bell leading the ringer says “Lead or first”, the bell in seconds place then says “second”, this progresses around the circle until all the ringers have said the number of the place they are ringing in.

Using variations to reinforce and to improve skills

Once the ringer is confidently ringing call changes and is:

- Striking accurately.

- Aware of their place in the row.

- Understanding the calls and not making mistakes.

Some variations can be added, this will develop skills and provide interest:

- Call by place in the row.

- Call and change at backstroke.

- Call by ringers names.

- Ring dodgy call changes – a call proceeded by a dodge. This variation demands an increased level of bell control to strike accurately and is a good exercise to use to work on accurate striking.

- Call from rounds directly into a known sequence such as Queens.

This requires an increased level of bell control but once the striking is good can be used for ringing at weddings and other occasions.

Calling call changes

This might well be a ringer's first opportunity to speak whilst ringing, which can be a lot harder than it sounds. Tips and exercises are given in the Understanding Call Changes online course. Remind them to speak loudly, speak clearly and speak at the right time. Give lots of feedback.

Start by asking the ringer to call the changes from outside the circle when they're not ringing a bell. When they call whilst ringing, ring a bell that doesn't move much and only move one bell one or two places and back again. Finally, ask other members of the band to randomly call changes and ask the ringer to call them back to rounds. Some very experienced ringers have difficulty doing that!

If they need help working out how to call to named changes, the following downloads will help:

Beyond call changes

2.6. Kaleidoscope Toolbox

Kaleidoscope ringing is a stepping stone between call changes and Plain Hunt. It provides variety and fun whilst not being too difficult to master. Kaleidoscope ringing differs from call changes in two ways:

- Each bell only moves one place (up or down) from its starting position – the ropesight is easier.

- The change continues to be made until told to stop – developing bell control.

Kaleidoscope ringing develops a sense of rhythm. Initially kaleidoscope sequences move out of rounds and back into rounds again. Because the sound of rounds is familiar it is easier for the new ringer to identify their bell and any gaps, clips or uneven ringing, allowing you to correct their striking until good, even ringing is established.

Explaining Kaleidoscope Ringing

Kaleidoscope ringing is a series of changes made within two places. There are three basic exercises. Each one demands a higher level of bell control than the previous one. They are best introduced in the order:

- Long places – four blows in one place.

- Place making – two blows rung in each place.

- Dodging.

Dodging requires a bell to move from place to place on every stroke (handstroke and backstroke). Good bell control is needed to strike the changes accurately. Dodging on heavier bells can provide an opportunity to practise adjusting the tail end position to speed up or slow down the bell. You might wish to download and print out the following cribsheets to share with your band of ringers when introducing kaleidoscope exercises:

- All about places and dodges.

- Some basic kaleidoscope works.

Striking a dodge accurately is a difficult skill to master. Why not look at our successful dodging tips to help you get there.

Using kaleidoscope exercises

Having learnt and successfully rung some of the easier kaleidoscope exercises the band can invent their own more complex sequences and give them a name.

Longer kaleidoscope exercisescan also be useful for ringers who want to practise pieces of work found later on in method ringing.

Kaleidoscope variations

There are a couple of named kaleidoscope exercises that will test you and your band. They can be rung for services and weddings, adding variety, whilst sounding interesting.

3. Covering Toolbox

Covering requires good bell control, an ability to ring steadily in one place, good listening skills, and ropesight. Most ringers use a combination of listening skills and ropesight to strike the tenor accurately when covering. These skills might develop together, or someone might start off with one sense doing most of the work. There is no right or wrong way for someone learning to cover. However, do remember to talk about and teach both.

Handling the tenor

Covering requires a novice ringer to ring the heaviest bell in the tower. If your student is unable to ring your tenor, then they can still get the benefits of learning to cover by using another bell which is called into the last place in the row. It might sound a bit funny but it will allow them to develop all the other skills that covering helps to build.

It is a misconception that ringing the tenor takes great physical strength, as it is in fact more dependent on technique. Plenty of slightly built ringers can be excellent tenor ringers because their bell handling is efficient. If the tenor is rung standing on a box this could also take some getting used to.

Whole pull and move to the right

As pulling off in rounds requires more forward planning with a larger bell, it’s worth spending some time polishing this skill before embarking on change ringing. Give your ringers plenty of opportunities to ring bells of different weights – moving gradually towards the front or the back, building up to ringing progressively larger bells.

Whole pull and stand

This is a game where all the ringers pull off in rounds, ring the following backstroke and stand on the next handstroke. This helps everyone practise pulling off in accurate rounds, and setting the bell.

A variation is to leave the tenor ringing steadily the whole time, so that everyone stands apart from the last bell. The other bells wait for two blows, then join in and ring rounds again. This affords an opportunity for the tenor ringer to ring consistently at a steady pace.

Teaching covering in incremental steps

Start by covering to bells moving just below the tenor in a regular manner:

- Making places

- Dodging

- Kaleidoscope exercises

- Plain Hunt

Once covering to Plain Hunt has been mastered, move on to covering methods. Different methods have different numbers of bells and patterns of bells coming to the back. These are listed in order of complexity (easiest first)

- Cloister Doubles with a Plain Bob start

- Cloister Doubles with a Grandsire start

- Plain Hunt Doubles

- Plain Bob Doubles

- Grandsire Doubles

Ringing steadily and listening skills

Practising ringing the tenor bell steadily is a good preparatory exercise, in rounds and call changes. Develop listening skills by counting the bell striking in the last place, hearing whether it is either late or early, then adjusting.

Try this exercise with your student. Stand behind the tenor whilst it is ringing rounds. The tenor ringer will adjust their speed to ring more slowly, or ring more quickly. Try to spot what happens to the ringing generally and how the other ringers adjust. Notice just how much the pace of the tenor can affect the ringing.

You can also stand behind someone who is covering to a method. The tenor will always be the last bell down, but see if you can notice any pattern to the bells that are being followed. Ask to see a diagram of the method afterwards, and compare this to your observations.

Developing ropesight

If you are ringing the tenor to call changes, you can maintain a steady rhythm using your listening skills, but try to spot the bells changing below you. Do you notice any pattern? Start with trying to spot the last bell down. As you get comfortable with this, you may find you increase the number of bells you’re able to spot and the order they fall. Don’t worry if this is not immediately apparent, most ringers develop this skill gradually over some time as peripheral vision develops.

Remember that even very experienced ringers don’t always know in advance which bell they will be ringing over at the back, they will ring steadily and just have an awareness of which is the last bell down.

Teaching using a simulator

To develop ropesight

Try turning the simulator sound off so that the ringer can cover a method purely by watching the screen and spotting the last rope down. Striking review is a great way to aim for a best personal score if they have several goes at this.

To develop listening skills

Turning the screen display off is a great way for ringers to appreciate that it’s not necessary to always know in advance which bell they need to follow, and to develop rhythmic striking just by listening. Making the tenor sound louder, or even substituting it for a different kind of sound, can help a ringer who is struggling to identify which is their bell.

To develop fine bell control

Use the ringing simulator to get the pull off in rounds really precise, perfecting this on bells of a variety of weights. This is a skill which is often overlooked on a practice night because ringers can be keen to let the rounds sort themselves out, then start ringing more complicated methods, but ringing nice rounds from the first pull off with the handstrokes and backstrokes in the right place is a fundamental skill for good striking. Explain that ringing the tenor, the ringer will need to start bringing the bell to the balance far earlier than on one of the lighter, front bells.

Learning using a simulator

Covering by watching using Abel

Covering by listening using Abel

4. Slow course methods

Slow course methods are a group of methods in which one bell rings a simple, repetitive pattern until a call is made. In a touch, each bell will take turns being the slow course bell, just as different bells go into the hunt in touches of Grandsire.

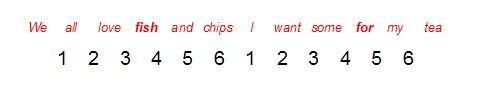

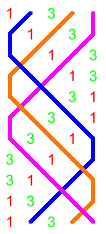

Brecon Place Doubles is shown on the right. It might initially look complicated, but if you look at the second (blue) it repeatedly leads for 8 blows and then makes seconds over the treble. That's a kaleidoscope exercise which is repeated whilst the other bells do the complicated stuff.

At a general practice, ringing slow course methods provides an opportunity for a band of mixed ability to ring plain courses together. A new ringer at the foundation level can ring the slow course bell which is like ringing a kaleidoscope exercise, with the additional challenge of ropesight as they will need to ring over and with different bells. Rather than sitting out watching kaleidoscope exercises, more experienced members of the band can join in and ring something that might be new to them, whilst supporting the new ringer.

The slow course methods in this collection vary in their degree of difficulty. A simple method like Brecon Bob Doubles has long leading with places made under the treble, whilst others have more challenging slow course work such as Welford Bob Doubles, where alternate long thirds and long fifths are made by the slow course bell.

From providing a little variety on a practice night to enabling bands to ring together without anyone sitting out, slow course methods are a fun way of developing skills and ropesight as a team.

Method progression

Methods are graded on difficulty of the slow course work, rather than difficulty of the method.

Entry level

Progressing

Tricky

Really Tricky

Method names

Whilst researching slow course methods we've found that some methods are given different names in Composition Library, Methodology and iAgrams. We refer to the Composition Library names, but please be aware of this potential confusion if you're looking up diagrams in the tower.

5. Method ringing

Having mastered plain hunt, a student may well want to start ringing methods inside. There is no set method to learn first, but ringers usually start with Plain Bob Doubles or Grandsire Doubles. Some bands ring mostly minor and will choose to take that route, however it is a slightly harder route, as there is no fixed bell (the tenor) to lead off. An alternative approach is to ring minimus methods (changes on four bells) with one or two covers.

Whichever method you introduce them to first, and whichever methods they then progress on to, they will need to develop two skills.

Understanding the theory

They need to understand the theory of whichever method they are ringing. This is a mental skill. Explain the theory to the student and ask them to consolidate this learning at home. There are apps for mobiles and tablets which can assist with this learning, along with the Method Toolboxes for Ringers resources.

Bell control

They also need to have the necessary bell handling skills to move their bell accurately during the ringing. This is a physical skill and can only be learned in the tower. Simulator practice is also useful to perfect technique.

5.1. How methods are written out

When someone starts to learn methods there is a host new theory to learn. They must also learn how methods are represented. Take time to introduce your student to the different ways of representing a method – what might work for you and have resonated in the past with others you have taught, might not work with someone else. The most common representations are:

- The blue line

- The circle of work

- The grid

- Place notation

Each of them contains the same information, just modelled in a different way.

What does someone need to know?

More information about each of these representations can be found in Method Toolboxes for Ringers. Whichever method is preferred, a student needs to know:

- The order of work, or the line.

- Placebells – how do they start on each bell?

- Treble landmarks – where they pass the treble and where relative to the treble does the "work" happen (typically for their first methods this is at the lead end).

- What happens at a bob and/or single.

Learning the theory

This will be the first time that a learner can accelerate their progress by learning the theory outside of the tower. Such revision should be actively encouraged, and students should also be introduced to ringing software and smartphone apps which can help them consolidate their learning. The Birmingham School of Bell Ringing identified the use of such apps as a key factor in accelerating a ringer's progress in early method ringing.

5.2. Successful dodging

Method ringing introduces the dodge, which takes practice to execute correctly. You will typically have to correct two problems:

- Poor striking, typically the bell is not moved sufficiently during the dodge.

- Not exiting the dodge in the correct direction.

Explaining the theory

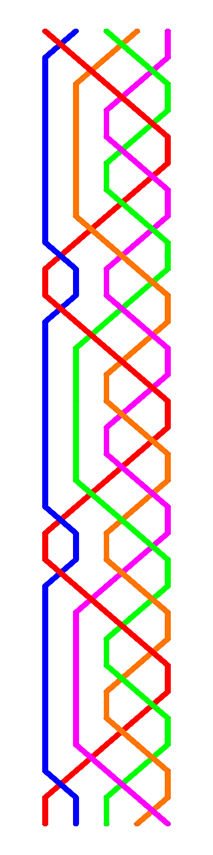

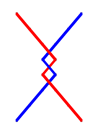

Start by explaining the theory and terminology of the dodge. Emphasis that the dodge is a single step backwards in plain hunt. If you're hunting down to the front, you step backwards for one blow and continue to hunt in the direction you were hunting before. The converse, for hunting up.

The diagram shows the line of two bells dodging. The bell represented by the blue line is ringing a dodge while hunting down. This is known as a down dodge. The bell represented by the red line is ringing a dodge while hunting up. This is known as an up dodge.

Practising dodging

You can give someone dodging practise using specific kaleidoscope ringing exercises or by ringing Treble Bob Hunt. Both concentrate the dodges into a small number of changes giving them plenty of practice and ropesight is simplified.

Bell control and striking in the right place whilst dodging

To dodge successfully a ringer needs to be able to change the speed of their bell at both handstroke and backstroke. At first you might have to tell them when to ring quicker or slower in order to strike their bell in the right place. However you should encourage them to start doing this themselves by using their listening skills as soon as possible.

If someone is having difficultly moving their bell to the correct place during the dodge, try some dodging practice and encourage them to exaggerate the movement of the dodge. Give plenty of feedback about what they are doing well, what they need to improve and how they do that. If necessary, explain and practice how they move the bell at handstroke and backstroke.

When dodging 3/4 down they are hunting down from the back – all the blows are quick blows with the exception of one:

- A quick blow at backstroke down in to 4th place

- A quick blow at handstroke down to 3rd place – put a little more weight on the rope

- A slow blow back up to 4th place at backstroke – put a little less weight on the rope

- A quick blow down into 3rd place at handstroke

- Then continue with the quicker blows to the lead

When dodging 3/4 up they are hunting up from the lead – all the blows are slow blows with the exception of one:

- A slow blow up into 2nd place at handstroke

- A slow blow up to 3rd place at backstroke

- A slow blow up to 4th place at handstroke – put a little less weight on the rope

- A quick blow down into 3rd place at backstroke – put a little more weight on the rope

- A slow blow up to 4th place at handstroke

- Then continue to hunt up to the back

Ropesight whilst dodging

Good ropesight whilst dodging takes time to develop. The first step is recognising which bell they are dodging with. They will always strike over this bell twice – at handstroke when dodging up and at backstroke when dodging down.

It is harder to see which bell they are striking over on the other stroke as this depends on the work that the other bell is doing. If they are finding this difficult ask them to study the method being rung by the other bells and learn what the pattern is. Eventually they will be able to see the bells without doing this.

5.3. Course and after bells

The concept of course and after bells is something that you can introduce when someone is learning to plain hunt or when they are learning to ring their first method. Some find it really useful, others find it just too much!

At some stage a new ringers will hear the expression “follow your course bell” and if you've not introduced the concept to them, they won't have a clue what this bit of bellringing wisdom means or what to do with it. Like a lot of things in ringing, the concept of coursing order and course and after bells is quite simple to understand but it is routinely very poorly explained, if it is explained at all.

Definitions

- Coursing is a way of describing how bells follow each other around in a method. One way to think of it is the order in which bells arrive at the front and the back.

- Your course bell is the bell that you course or follow down to the lead – so you might hear someone say “take your course bell off the lead.” The bell ahead of you when you arrive at the lead, or the back is your course bell.

- Your after bell is the bell that follows you down to lead – hence the instruction “your after bell takes you off the back”. This is the bell behind you, which leads after you, or arrives at the back after you.

Examples

The definitions are very dry, and it is probably easier for students to understand the concepts using an example or by drawing out Plain Hunt in different colours. It's actually a lot easier to see the concept by illustrating with more bells – six being the minimum.

In Plain Hunt the bells come down to the lead in a certain order. In this example (on the right) we are showing Plain Hunt on five bells.

- Your course bell is the bell you ring over before you lead.

- You take it off the lead.

- If you are ringing the 4 it is the 2.

- Your after bell is the bell you ring over in 2nd place after leading.

- It takes you off the lead.

- If you are ringing the 4 it is the 5.

Supporting resources

- Course and after bells – cribsheet

- Plain Hunt worksheet – writing out the grid

- Course and after bells – a game

Extending into methods

Developing an awareness of course and after bells when ringing is helpful later on when progressing on to ringing methods. Your course bells are the same whichever method you are ringing. However when you meet them and what work you do with them varies with the method you are ringing. Your course and after bells will change when a bob or single is called.

Knowing which bells are your course and after bell helps you ring in the same way that knowing the work you do with the treble helps you ring:

- If you know that you are doing a piece of work with one of these bells then you don’t have to worry so much about ropesight.

- It gives reassurance – you’re in the right place.

- If you’re not quite sure then knowing how you work with your course and after bell can help you get it right.

6. Minimus Toolbox

Methods that are rung on four bells are an excellent introduction to method ringing. They are quick to ring and with only three other bells to watch, the ropesight is easier to aquire.

However, change ringing on four bells is quite physically demanding, requiring larger changes of speed. It therefore helps develop the habit of forward planning in placing a bell correctly. On lower numbers, changes of place in the row need to be made well in advance – the larger gaps between blows make it less easy to quickly adjust where the bell strikes. Ringing well on four bells is an excellent test of bell handling, striking, and thinking ahead.

Although there are fewer methods available for four bells, each one offers a new challenge and introduces concepts such as awareness of treble passing, dodging, ringing a reverse method, understanding a double method, making internal places, wrong-hunting, counting blows, striking and ropesight.

Standard plain minimus methods do not require any calls to ring a full extent as all 24 possible changes are rung in a plain course.

Methods

The standard 11 minimus methods are: Plain Bob, Reverse Bob, Double Bob, Canterbury, Reverse Canterbury, Double Canterbury, St Nicholas, Reverse St Nicholas, Single Court, Reverse Court and Double Court.

There are plenty more types of minimus methods to explore which are less commonly rung, including principles, alliance methods, treble bob methods, differential methods, twin hunt methods and methods which don’t have palindromic symmetry.

Supporting resources

- Successful dodging – what is a dodge and how to strike it successfully

- How are methods written out?

Method Progression

Entry Level

Progressing

Tricky

Really Tricky

7. Plain Hunt Toolbox

Plain Hunt will probably be the first time that someone will have to move their bell at every change. It is the simplest form of change ringing but it will require the ringer to learn and apply various new concepts, all at the same time:

- They will have to remember a sequence of places – there is no conductor telling them which place to ring in, as happens in call or kaleidoscope changes.

- It is important that they know in which position in the change their bell is ringing, and helpful to be aware of which bell they are following (known as ropesight).

- This may be the first time that they will need to adjust the speed of their bell at every stroke, moving at both handstroke and backstroke.

- Unlike call changes, all the bells change position (place) in the row on each and every stroke, except when leading or lying when they ring two blows in the same place.

Teaching the theory

How to set up a Plain Hunt workshop including theory session.

For one-on-one teaching you can use the workshop presentation and provide the student with the cribsheet:

Teaching aids

Learning aids

Stepping stone methods

Plain Hunt on 2 bells

Plain Hunt on 3 bells

Plain Hunt on 4 bells

Plain Hunt on 5 bells

Teaching course bells

For some students, now is a good time to start introducing the concept of course and after bells. Tips and resources can be found here.

Solving common problems

Teaching using a simulator

How to set up a simulator to teach Flying Dutchman by adding a composition.

Changing the volume of a single bell

This will help the ringer to pick out the sound of theirown bell. Later on in their learning journey they might wish to increase the volume of the treble so that they can hear its position in the change.

Using ropesight flashes

This is probably the simulator equivalent of a live ringer "giving the nod" helping to pick out when a ringer should be following them in the change.

Beyond Plain Hunt Doubles

8. Plain Bob Doubles Toolbox

Plain Bob Doubles is often one of the first methods that a new ringers learns after they have mastered Plain Hunt. The treble plain hunts up to fifth place and back and there are four working bells which complete a cycle of four pieces of work. Often it is rung on six bells with the tenor covering. This gives a visual and auditory cue to help accurate leading.

There is more to learn to ring a plain course than in Grandsire Doubles but touches are simpler. The plain course is four leads long, compared to three leads for Grandsire Doubles.

The dodges in Plain Bob are very different to those in Grandsire:

- Plain Bob Doubles – the 3-4 dodge requires the "step back" to be made at backstroke.

- Grandsire Doubles – the 4-5 dodge requires the "step back" to be made at handstroke.

Switching between the two methods can be confusing unless the learner rigorously counts their place and has learnt when the "step back" or dodge is made in each method.

Teaching the theory

How to set up Plain Bob Doubles workshops including theory sessions.

Use these notes and either the cribsheets or the workshop presentation as visual aids.

Learning aids

Download these cribsheets for further study or for use in the tower.

Learning aids

- Plain Bob Doubles dominoes

- Plain Bob Doubles happy families

- Plain Bob Doubles crossword

- Plain Bob Doubles wordsearch

Supporting resources

- Successful dodging – what is a dodge and how to strike it successfully

- How are methods written out?

Practice night touches

For those who don’t do much conducting, being asked to call and keep other ringers straight may seem quite daunting. Here are a some simple, short touches you can call with your ringers to help them learn what to do at the call bit by bit.

If you wish to learn how to call yourself, search for the First steps in calling bobs online course.

Teaching using a simulator

How to set up a simulator to teach Bistow Doubles using MicroSIRIL

How to set up a simulator to teach Penultimus Doubles using place notation

How to set up a simulator to teach touches of Plain Bob Doubles

Beyond Plain Bob Doubles

9. Grandsire Doubles Toolbox

Grandsire Doubles has two bells that plain hunt so it has only three working bells (the 3, 4 and 5 in the plain course) and therefore only three pieces of work. There is less to learn to ring a plain course than Plain Bob Doubles but touches are more complex. Because the second plain hunts throughout, the plain course is only three leads long, compared to four leads for Plain Bob Doubles.

The dodges in Grandsire feel very different to those in Plain Bob. In:

- Plain Bob Doubles – the 3-4 dodge requires the 'step back' to be made at backstroke.

- Grandsire Doubles – the 4-5 dodge requires the 'step back' to be made at handstroke.

Switching between the two methods can be confusing to a new ringer, unless they rigorously count their place and have learnt when the "step back" or dodge is made in each method.

Learning aids

Teaching the theory

How to set up Grandsire Doubles workshops including theory sessions.

For one-on-one teaching you can use the workshop presentation and provide the student with this cribsheet:

Stepping stone methods

Learning Aids

Calling Grandsire

Touches of Grandsire contain both bobs and singles. The call is made at handstroke when the treble is in thirds place hunting down to the front. It takes effect the following handstroke which is one blow earlier than in Plain Bob Doubles.

Practice night touches

For those who don’t do much conducting, being asked to call Grandsire and keep other ringers straight may seem quite daunting. Here are a few tips that might be helpful on a practice night.

Beyond Grandsire Doubles

10. Exploring doubles methods

Once your student has mastered Grandsire and Plain Bob Doubles there is a whole world of doubles ringing for them to play with. There are lots of new methods to learn and then variations to explore. Learning and ringing doubles methods and variations can become a project for the whole band.

Doubles methods

Concentrating first on doubles methods, there are groups of methods in which each method has a native type of call. You've seen that already – a Grandsire bob is very different to a Plain Bob bob. So, with each method you also need to learn which bobs or singles belong to the method. Methods are grouped into the type of bob used, e.g. a Plain Bob bob or a Reverse Canterbury bob.

Sounds a bit complicated, but just like any other form of ringing if you start learning the methods in a logical progression, it's easier to see what's happening and slowly add to your method repertoire. Most people start by learning Reverse Canterbury which is very closely related to Plain Bob.

Doubles variations

As a way of extending their doubles repertoire, many enjoy ringing variations. These are usually standard doubles methods, rung with a call that is normally associated with a different method. For example, St Simon’s Doubles rung with a Reverse Canterbury bob is called Eynsham. If it’s rung with an old single (or Plain Bob single) it’s called Cassington.

Doubles variations do not usually take very long to learn, but they can be interesting to call and require fast reactions, especially if they involve more than one type of call in each extent.

If there are only five ringers and the band would like a bit of variety, ringing variations is good fun. Ringers who regularly ring variations usually develop fast mental agility and an ability to respond to treble passing positions as the work comes round quickly and is constantly changing.

Learning aids

Conducting doubles methods

- Conducting All Saints

- Conducting April Day

- Conducting Reverse Canterbury

- Conducting Reverse St Bartholomew

- Conducting the St Martin's group

- Conducting the Winchendon Place group

Method progression

Getting going

Progressing

St Martin's group

Methods rung with Plain Bob bobs. Each method has a different front work.

Winchendon Place group

Methods rung with Reverse Canterbury bobs. The front works for each method are exactly as for the St Martin's group, but these are rung with places in 3-4, different bobs and the 3 and 4 starts are different.

11. Plain Bob Minor Toolbox

Plain Bob Minor is a widely rung method on six bells and a common progression from ringing Plain Bob Doubles. As the tenor rings the method rather than covering, there is no longer a constant visual and auditory cue to help accurate leading.

Lying behind is made at handstroke and backstroke, which will feel different from the backstroke and handstroke lie in Plain Bob Doubles.

Teaching the theory

How to set up a Plain Bob Minor workshop including theory sessions.

For one-on-one teaching you can use the workshop presentation and provide the student with the cribsheet:

Stepping stone methods

Learning Aids

Additional Theory

If the theory of course and after bells wasn't discussed at the plain hunt stage, now would be a good time to teach it. Tips and resources can be found here.

Calling Plain Bob Minor

Calling Plain Bob Minor introduces concepts such as wrong and home which are used in other minor methods and their extensions on higher numbers.

Practice night touches

For those who don’t do much calling, being asked to call and keep other ringers straight may seem quite daunting. Here are a some simple, short touches you can use with your ringers to help them learn what to do at the call bit by bit.

Beyond Plain Bob Minor

12. Stedman Doubles Toolbox

Stedman is a principle that is rung in many towers, and at some stage a ringer will want to ring it so they can join in. It extends easily to higher numbers and offers opportunities for many musical compositions.

Stedman will probably be like no other method they have rung before. Partly this is due to it being a principle with no treble to look out for or even a lead end. The leading will also feel unfamiliar: sometimes they will lead at handstroke followed by backstroke (leading right) which is what they will be used to; sometimes they will lead at backstroke followed by handstroke (leading wrong) and sometimes for only one blow at either handstroke or backstroke (snap lead). All of this leads to some interesting leading challenges.

When learning the method it is very useful for a ringer to know which leads are right and which ones wrong.

Teaching the theory

How to set up a Stedman Doubles workshop including theory sessions.

For one-on-one teaching you can use the workshop presentation and provide the student with this cribsheet:

Stepping stone methods

The following stepping stone methods allow your student to practise parts of Stedman Doubles before putting them together to ring the complete method:

You might wish to practise wrong hunting with the student which will allow them to get the feel of leading wrong. The easiest way of doing this is to ring Plain Hunt with the bells starting by hunting the opposite way to normal:

- The treble makes one blow in lead at the handstroke before hunting to the back.

- All other odd bells hunt down to the front.

- The even bells hunt down up to the back.

Learning aids

Calling Stedman Doubles

As a teacher you might very well have to call touches of Stedman Doubles.

The only call used in Stedman Doubles is the single. The single affects the bell about to double dodge 4-5 down and the bell leaving the front, and has the effect of swapping the bells in 4-5. The bells doing the frontwork are unaffected.

Calls are made at handstroke and are made two blows before a six end. The download indicates all the calling positions.

Quick or Slow – which way do you go in?

The question of whether to go in to the frontwork quick or slow provides many opportunities for confusion in Stedman, especially after a call. Ringers have different preferred ways of remembering, from moving their feet in certain ways to watching for a particular bell in the coursing order.

You can help your ringer get this right, by providing them with some tips that might help:

- Unless there has been a call, they will be doing the opposite of what they did last – if they went in quick last time, it will be slow and vice versa.

- If the bell which they double-dodged with in 4-5 up (their course bell) passes them as they move from 4-5 down towards the lead they must be a slow bell (because it was a quick bell). The converse is true, if it is still on the front it was slow bell so they must be quick bell.

- When they are hunting down from the double dodge in 4-5 down, if the bells are leading right (handstroke and backstroke) its a quick six so the next one will be a slow six – they will go in slow – and vice versa.

- As a last resort – as they move from thirds place towards the lead they will follow each of the two remaining bells one after the other. That may mean holding in thirds if the two bells swap places, meaning they go in slow. If they didn't hold in thirds they go in quick.